The Imperial Spa (Kaisersbad / Císařské lázně) is one of the largest and artistically richest spa houses in Karlovy Vary. A new peat spa was built on the site of the former Baroque brewery in the period of 1893 – 1895, following the plans of the well-known Viennese architectural partners Ferdinand Fellner and Hermann Helmer. The interior of this spectacular building, built in the historicist style of the French Neo-Renaissance, conceals magnificent details combined with unusual comfort and exceptionally modern technical provisions for its era. In the front section of the building are public halls, parlors, and waiting rooms, where the spa’s clientele used to wait for their procedures or could rest once they were finished. The atrium, i.e., semi-circular part of the building, is surrounded with a ring of bathing cabins. On the 1st floor in the central buttress is a large hall, called the Zander Hall, where equipment for Swedish gymnastics was installed in line with the principles of Dr. Zander’s exercise method. The dispositional facilities of the spa’s operations were absolutely unique: a total of 120 bathing rooms, the most valuable and precious of them being the Princely Bath (Fürstenbad). Situated on the right side of the pavilion’s front section, it was reserved for the most prominent guests. The spa’s provisions included a luxuriously decorated changing room (powder room) and resting room. All other bathing rooms, both on the ground and upper floor, had their own individual changing room and cabin. Particularly special, and indeed unique, was the system of preparing and delivering peat to the individual bathing chambers. The peat was prepared and mixed for the spa in a separate building, following the ingenious solution of Fellner and Helmer based on the concept that everything that might disturb spa operations at the Imperial Spa was concentrated in a separate facility. The bathing procedure progressed as follows: A cart containing peat was pushed into the basement of the building to the rear, where it was emptied into a pit situated above the entrance to the building. From there, it was immediately lifted and forwarded onward for sorting, i.e., cleansing. Then, the clean peat was dropped into a system of pipes connected to six large wooden mixing barrels, where it was mixed with water using mechanically propelled mixers. The operating personnel in the basement would pull up the wooden bathing tubs and fill them up with the peat, using a pulley from the mixing barrels through draining spouts…..

Author: Dagmar Slámová

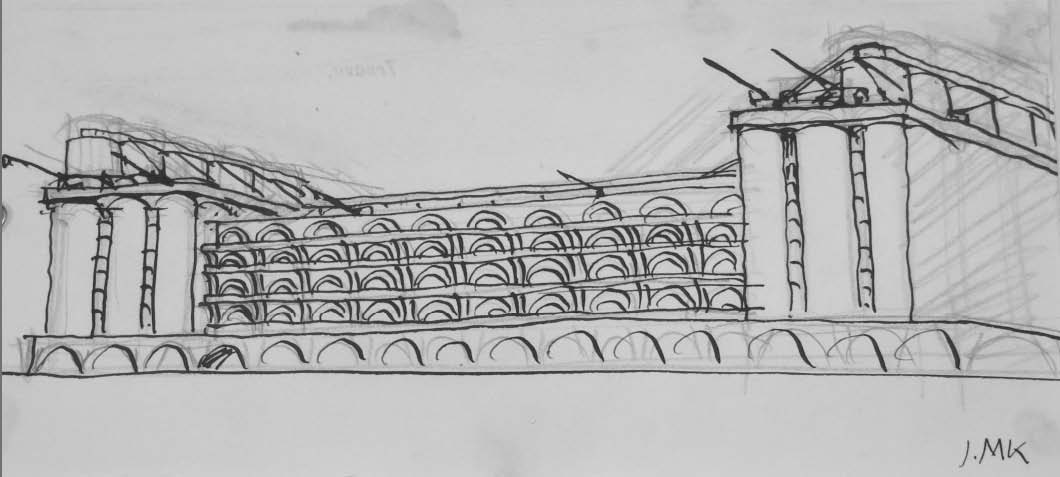

From Technical Beauty to the Medern Aesthetic and Back: Unrealised Industrial Buildings of Josef Marek in the Context of Modern Architectural Development 1900 – 1939

The present contribution addresses the analysis of the industrial buildings designed by architect Josef Marek during the 1920s against the background of the era’s discourse on the development of modern architecture and its mutual relations with industrial construction as its specific yet at the same time integral component, not only as the bearer of technical mastery but no less of its own aesthetic values.Born in Petrovice in Moravia, Josef Marek arrived in Slovakia as part of the generation of Czech architects to settle there after the founding of the first Czechoslovak Republic in 1918. His previous activities and studies on the Czech side of the state are still shrouded in mystery, and we do not even have any clear idea as to the circumstances of his settling in Trnava. It is, however, known that he studied architecture at the Prague Academy of Fine Arts under Jan Kotěra, graduating in 1914.Knowledge of the architectonic oeuvre of Josef Marek has long been superficial and insufficient.Moreover, very few scholars would classify him as a designer of industrial structures. However, we must recall that a thorough knowledge of an architect’s legacy should include not only realized buildings, but the entire range of study sketches, unrealised projects and competition entries. In this sense, we can find support in a range of instances involving other architects who – despite the creation of a body of work of international fame – are regarded a priori as having nothing to do with industrial realisations, yet are found, in a systematic study of their work, to have been greatly fascinated by the theme of industrial building design, and even to have created highly mature projects in this area at a quite early stage in their careers. One example is no less of a figure than Le Corbusier (1887 – 1965). Marián Polášek (*1932), a Slovak architect involved with industrial architecture not only on the level of realisations but also in terms of its theory, has determined Le Corbusier to have been the author of the never-realised projects of two exceptionally advanced industrial buildings with Functionalist elements – the food-processing works in Challuy and Garchize from 1917 – 1918.A similar opportunity for Slovak architectural history is presented by the chance to find work of this kind within the creative legacy of Josef Marek, which uncovers new correspondences in our view of his oeuvre, but above all documents his changes of viewpoint derived from his study of contemporary art, architectural creation, and the theory of all architectural areas, including industrial structures, even though most likely none of his designs were ever built….

Technical Objects in the Complex of the TBC Sanatorium in Vyšné Hágy

During the interwar period, when the prevalence of tuberculosis rapidly increased, one of the largest and most modern TBC sanatoriums in Czechoslovakia was constructed in a remote location in the High Tatras. Arising on apreviously vacant site above the settlement of Vyšné Hágy, this complex of buildings is one of the most impressive realizations of Czechoslovak functionalist architecture, designed by the Prague architects F. A. Libra and J. Kan. Intended for the hospitalization of infectious tubercular patients, the sanatorium was deliberately isolated in the High Tatra forests, where it worked as a self-sustaining urban complex. The complicated and demanding organization of this outstanding health care facility was provided by several service objects subordinated to the function of the main medical building. Consequently, an exceptional opportunity arose for technical architecture in the unexpected setting of a protected alpine-forest. Most notable here is the boiler-house with its high chimney, functionally and architectonically connected with almost all the objects of the sanatorium through the heat collectors. In the end, it emerged as itself an expressive landmark. The central boiler-house was a key element for the smooth functioning of the sanatorium, and it greatly supported the self-sufficiency of the medical complex. From the beginning, it has covered several functions. Besides the central heating, it provides a supply of warm water, as well as electric energy produced in the incorporated steam power station. Steam from the boiler-house was used in the steam-laundry, for heating the greenhouse, for preparation of food in the kitchen. At the same time, a waste incineration plant and the quarters of the operator were also situated in the building of the boiler-house.Designing a combined boiler-house and steam power station in the protected forest of the High Tatras was an architecturally difficult commission. During the process of design, a major technological transformation occurred that significantly changed the final appearance of the boiler-house’s architecture. Besides the technological conditions, the final architectonic design was shaped by F. A. Libra’s recent experience with the project of the functionalist building of the Edison transformer station in Prague. The boiler-house was incorporated into the complex through an electrified railway siding (used for coal delivery), only fragments of which are still preserved. Moreover, the boiler-house was also connected by with the main medical building. Wagons delivering freshly prepared food entered the basement of medical building through the 170 m long vaulted tunnel, which is itself an interesting technical work….

The Industrial Heritage of the Dynamitka Works Versus Traditional Heritage Conservation

Update the Theoretical Basis

Conservation of industrial heritage is often confronted with issues which it is seemingly unable to solve in practice. In Bratislava, the premises of Istrochem – the former ‘Dynamitka’ dynamite factory – clearly highlight this situation. Due to the contrast between its current state and its attributed historical importance, the complex represents a good example for examining not only the tools of the current conservation profession, but also the adequacy of its existing theoretical background. An explanation for the greater importance of focusing on such a problematic example, instead of a successful project of restoration/re-use that leads to conservation of a specific industrial building or site, is that a negative example encourages the effort to understand the deeper context from which these problems arise. The issues of industrial heritage conservation are often simplified and reduced to two extremes: either through a positive example – the re-use of a specific industrial monument, in which attention is focused on the visual appeal of industrial architecture, or negatively as a conflict of interests among different stakeholders, whether owners, investors or preservationists. Questions of a deeper context regarding the importance and possibilities of industrial heritage conservation, or the immediate factors that affect its sustainability, remain hidden. Partially, this situation has emerged because the primary examples of successful conversions in Slovakia are small-scale works initiated by conscious individuals, and hence are not the results of systematic planning. In consequence, sufficient experience is lacking for replication and application in more complex situations. The series of unfortunate cases of demolition of industrial heritage that have occurred in Bratislava in recent years are the reason why it is especially important to uncover the roots of the problem, even if, in absolute terms, there are now many fewer industrial monuments left to protect. The following paper aims to point out that the issue is not simply the conservation and re-use of specific monuments – in this case the Dynamitka works – but the formulation of a theme that enables to think on a more general level about the importance for society at large of the built traces left by specific historic eras. Dynamitka, a factory established in 1873 by the famous Swedish inventor Alfred Nobel, has undergone significant transformation since its creation, as the result of major historical events, including two world wars. Both the political and the economic changes highly influenced the factory’s production program, and as a consequence increased the diversity of the physical structures on the site….

The Lusatian Lakeland

An Eastern German Project for the Transformation of an Industrial Opencast Mining Landscape

The end of the GDR regime raised the question in the federal states of Brandenburg and Saxony in the east of Germany of what to do with the devastated lunar landscapes in the Lusatian mining district and the opencast mines which were suddenly no longer needed. The popular view, which soon became widespread, was to eliminate all traces of the legacy of the industrial and mining past as far as possible, demolishing all the briquetting factories, coking plants and power stations as well as all the chimneys, in an attempt to bury the memories of polluted air, soil and water long with their physical remains. The vast opencast pits were to be reinvented as lakes for swimming and boating, as planned by the proposal of the Mecklenburgische Seenplatte or Mecklenburg Lake District.From an economic point of view, the long-term focus in the east of Germany, Lusatia naturally included, was on prolonging the industrial policy and the promotion of business development as instruments which had stood the test of decades. Consequently it is no wonder that in the Saxon part of Lusatia, the “Karl-May-Land” project was initiated, a large-scale post-mining landscape development project aimed at creating the illusion of an American Western landscape of Indian reservations and open prairies. However, such projects hang by “30 threads”, and if just one of these threads breaks (the investor pulls out, the government funding does not materialise, the water doesn’t rise as planned…), the whole project is shelved – as happened in the end.The Internationale Bauausstellung (IBA) Fürst-Pückler-Land (2000 – 2010), by contrast, had 30 projects and therefore 30 feet to stand on, which could support and stabilise each other. The initiators of the IBA Fürst-Pückler-Land staked everything on a large number of smaller individual projects, on endogenous potential, and on networking and cooperation between the key players in the region. The vision was for Lusatia to become a workshop for new landscapes, providing the resources for a new type of man-made environment to emerge from the post-mining landscapes. In short, the aim was an environment that does not disown its industrial past and acts as a vehicle to carry the long tradition of innovations in engineering through to the modern era.As far back as 2009, the IBA conference “Post-Mining Landscape” confirmed that although there may be more spectacular projects in other places, it was the first time that anything had been undertaken on this scale anywhere in the world, with 30 individual projects involving the local people and following a clearly-defined philosophy of the recreation of a landscape laid waste….

Automomous Universality

Attempts at Systematization in Hungarian Industrial Architecture in the Early Kádár Period

The systematisation of planning and implementation in industrial architecture, which encompassed a rapidly changing and broad range of building types, was a crucial issue in Hungary throughout the two decades after World War II. The architects of the state-owned Industrial Building Design Company (Ipari Épülettervező Vállalat, IPARTERV), which was established in 1948 and employed a staff of over one thousand, strove to apply unified planning methods or implementation techniques to the diverse area of industrial architecture, while always adapting them to the given state of the economy and the building industry. This uniformity inevitably resulted in constant professional conflicts arising from economic, functional and artistic issues, which later intensified especially in the first decade of János Kádár’s political regime, after the collapse in 1956 of Mátyás Rákosi’s Stalinist dictatorship. At the same time, the extraordinary structural innovativeness and architectural creativity bred by the period’s political and economic turnover in the area of industrial architecture played a fundamental role in the ‘selfrehabilitation’ of Hungarian modernism that took place after the years of Stalinism.

ON-SITE PRECASTING: FROM DOMINANCE TO INTEGRATION

It was in the first years of the Kádár regime that a new comprehensive industrialisation programme was launched in the spirit of social modernisation. Closely connected to the ambitions of the period between 1956 and 1963, generally referred to by Hungarian historians as the ‘early Kádár period’, the programme was aimed at political stabilization and the correction of the grave economic mistakes of the Rákosi dictatorship. Initially, the economic policies of the new regime were based on the principle of a more temperate industrialization (intensifying in nature, it gave preference to light industry and the processing industries, tailored to the country’s characteristics), but after 1958 – related to the internal party policies aiming towards radically improving the living standards of the population, as well as the production cooperation programmes within the COMECON countries – the emphasis was again shifted to supporting the extensive development of heavy industry, as well as the chemical and building industries…..

Value Saving and Community use Regarding Urban Renewal

Protection of Hungarian Industrial Heritage and Possibilities for its Reutilization at the Turn of the Millennium

INDUSTRIAL CULTURE AND IDENTITY

The culture of manufacture has its roots in everyday life. In the guild manufactories renowned in history, and later within industrial working-class families, traditions of expertise, working methods and special techniques have been passed down from generation to generation. Beside the concentrated placement of factories, capitalist industrial development also brought about residential colonies. The residents of the workers’ settlements formed autonomous communities, where closeknit of life involved a strong feeling of togetherness, implying that cultural conventions generally remained within the community. Consequently, it could be interesting to examine these enclosed workers’ settlements, since in this way more information can be obtained about the larger industrial area and its operation. The collective memory of traditional industrial towns holds a wealth of still unknown knowlege that could be lost in a short time in case of the closure of the industrial building or factory zone, and without conscientious collecting work it could vanish /1/. The exact knowledge of the applied processes and mechanization was linked to specific towns or regions, thus determining their identity for a long time. Industrial heritage protection pays concentrated attention to the protection of immaterial factors alongside protecting the physical manifestation of industrial activity, the building stock. The importance of such factors has grown significantly due to the rapid technological and social change of the 20th century. The memory of the people plays an important role in this study, since the abandoned buildings and machines are difficult to interpret without written or authentic pictorial sources, and provide a less informative picture regarding their use. Authentic heritage protection covers not only the protection of the localized material remains, but also takes the mobile and spiritual heritage into account. Thus the industrial area and the industrial building in the narrow sense – compared to other types of monuments whose usage still haws a living culture – require the application of significantly more complex criteria to be taken into consideration…

Industrial architectural heritage – re-evaluating research parameters for more authentic preservation approaches

1. INDUSTRIALISATION – IMPACTS ON THE DEVELOPMENT OF ARCHITECTURE AND SPACE

In terms of social development, industrialization represents the greatest change of all, not only because of the altered methods of production, but also because of its effects on all aspects of life. Industrialisation or the Industrial Revolution, as it is often called due to the intensive changes that occurred over a short period of time, primarily means the transformation of production processes. Handcrafts were replaced by large-scale production, resulting in the fall of prices for manufactured goods and the growth of wider consumption, which touched on almost every aspect of life. The changes were first evident in the organisation of manufacturing and the design of production facilities and sites; in the next stages, industrialization dominated the tempo of social development and hence spatial development as well as architectural development. The latter change was reflected in the emergence of many new building types and a fundamental shift in basic design principles, as established by Modernism in Europe starting between the World Wars.This chapter will discuss only some of the most significant cases, illustrating events began most intensively in the British Isles and later came to Continental Europe, spreading from the West to the East. The Central European and more specifically the Slovenian territory, which is the main focus of my studies, saw the beginnings of the Industrial Revolution in the second half of the 19th century, after the Austro-Hungarian Monarchy built the Southern Railway, which linked Vienna and Trieste in 1857.The development of Slovenian industrialization and the resulting industrial architectural heritage until the end of the 20th century can be divided into five periods. The first one is characterized by early industrialisation and the operation of the world-renowned mercury mine, most intensively from the 16th century until its closing at the end of the 20th century; in 2012, the site was inscribed on UNESCO’s World Heritage List. The early industrialization took place from about the mid-18th century until the arrival of the railway; it represents a stage when ironwork centres and companies from different industries came into existence. A distinct reversal was the building of the aforementioned Southern Railway, when the intensive second stage started. One of the development peaks was experienced as early as in 1863 when the Suedbahn Railway Company built the complex of workshops for repair and supply of trains in Maribor, including a workers’ settlement, over an area exceeding 84.400 m2. Industrialisation was no less intensive in the Zasavje coal-mining region, where coal mines were opened alongside, and supplying, the railroad….

Vibrations in the Iinterlude

A few Notes on the Current Situation of Post-War Industrial Aarchitecture in the Czech Republi

The increasingly frequent attempts to point out the importance of industrial buildings and the possibility of their use in a new perspective have, through expert discussions, publications, exhibitions and through various initiatives of a number of groups and associations as well as reports in mainstream media, contributed to a significantly increased awareness of the value of industrial heritage in recent years. However, while our attention has often been drawn to the architecture of the 19th and the first half of the 20th century, we still perceive post-war industrial buildings as something anonymous and vague which – to top it all – saw the light of the day at the wrong time. The source of our uncertainty is mainly caused by the close historical proximity, as well as the complicated social and ideological situation or even our own prejudice and insufficient differentiation. But if we take a closer look at this specific architecture and the context of its origins, we discover a number of aspects challenging our opinion.The aim of the paper is to outline the current situation of this previously unmapped layer of our architectural heritage, offering a selection of the most interesting buildings created between 1945 and 1980 which are either already lost to us, in imminent danger of vanishing or which have been given an opportunity to be used in a new context. The text is one of the results of the research performed within the dissertation titled Industrial Architecture in the Czech Republic: 1945 – 1960 (Architektura průmyslových staveb v České republice, 1945 – 1960), currently carried out at the Faculty of Architecture, CTU, Prague, and the project by the Ministry of Culture of the Czech Republic implemented under the “NAKI” (National and Cultural Identity) applied research programme called the Industrial Topography – new use of industrial heritage in the Czech Republic as a part of national and cultural identity (DF11P01OVV016), investigated from 2011 to 2014 by the Research Centre for Industrial Heritage, Faculty of Architecture, CTU, Prague.

Editorial

Recently, architectural discussion in Slovakia has been stirred by the dramatic wave of demolition of industrial heritage from the previous century. One after the other, the entrance building to the Ružomberok paper works, the former grain mills in Nitra, and even the disused thread works and the Stein brewery in Bratislava have fallen to the wrecking ball. Yet the views of the professional community in this area, though, are far from unified. Indeed, quite the opposite: these interventions in former industrial complexes have almost completely polarised the professional community. These ambiguous attitudes stem not only from the absence of a deeper knowledge and evaluation of the heritage values of this architecture, but also the lack of clarity in strategies for its potential protection and renovation. Although views on the architectural heritage of the industrial era have been in continuous evolution since the formation of the field of industrial archaeology in the 1950s, unambiguous answers on why and how to conserve this heritage have not yet permeated into general public awareness. Industrial heritage conservation remains a field that seemingly concerns only a limited group of experts, supported by individuals with a personal connection to the industrial production – mostly former employees of the works, or specific enthusiasts.Despite the growing interest in industrial heritage, the conservation of which is promoted by the International Committee for Conservation of Industrial Heritage (TICCIH) along with other organisations and heritage institutions, it would seem that little agreement exists as to what common benefit is provided through the protection of these buildings. Not even the evidence of dozens of conversions that have brought fading structures back to full life again reveal with clarity which particular factors can bring a project to successful completion.The current global situation, characterized by economic and ecological crises that can be considered a direct consequence of the ruthless pursuit of individual interests, mass production and consumption over the last century, offers a a good occasion to reflect on the essence and meaning of industrial heritage. Such a reflection becomes even more urgent when observing that a number of monuments are balancing on the brink of extinction and right now is probably the final chance to make an effort to save them.The immediate need to revaluate the approach to industrial heritage is equally emphasized by contributors of the publication Industrial Heritage Re-Tooled (DOUET, ed., 2012), issued by TICCIH….

UNDER THE SKIN OF MONUMENT CARE

26 – 29. April, 2021

Held by: Institute of Art History – Czech Academy of Sciences. Institute for the Study of Totalitarian Regimes, National Heritage Institute, Institute of Contemporary History – Czech Academy of Sciences

Available online at: https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=r4CSpIGxk98

THE HYBRID IMAGE OF A HYBRID CITY

HENRIETA MORAVČÍKOVÁ, PETER SZALAY, KATARÍNA HABERLANDOVÁ, LAURA KRIŠTEKOVÁ AND MONIKA BOČKOVÁ

BRATISLAVA (NE)PLÁNOVANÉ MESTO

BRATISLAVA (UN)PLANNED CITY

Bratislava: Slovart, 2020, 622 p.

ISBN: 9788055646961

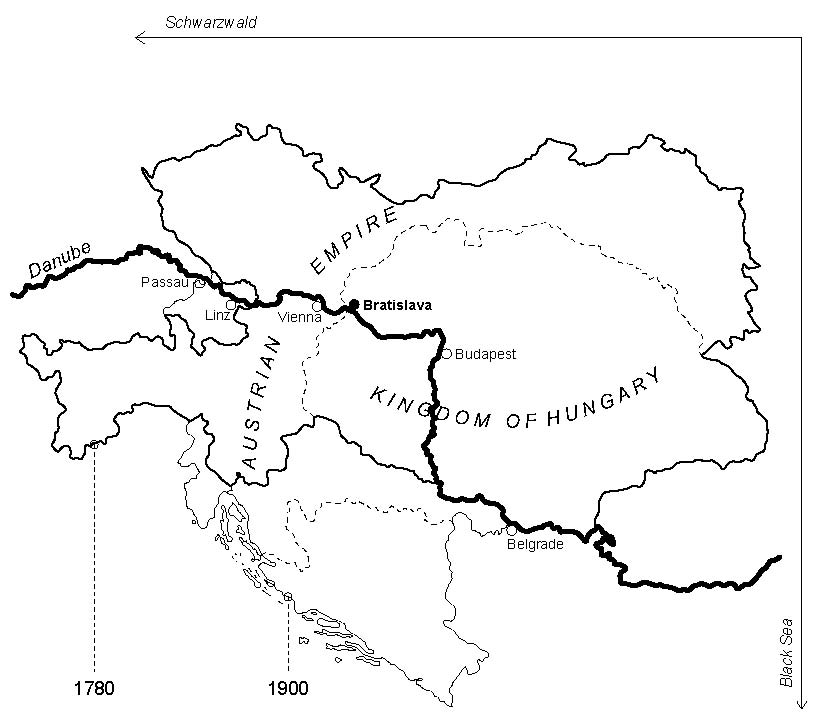

Bratislava and the Planned River: Mapping the Impact of the Danube Regulations between 1772 and 1896 on Urban Development

The current pattern of the Danube is a result of human activity as well as natural changes. Throughout history, different riverine transformations have affected the urban structure of Bratislava. The paper deals with the period of regulations between the years 1772 and 1896. To analyze the river as a natural and cultural phenomenon, a hybrid method was used. Selected aspects of historiographic research were interpreted on the basis of historical maps in the form of mapping. The method shows that local interventions were mainly part of the greater vision of the navigable waterway in Austria-Hungary.

The Work of Karel Boublík

The article presents the first detailed examination of the life and work of Karel Boublík (1869 – 1925), a Lviv architect of Czech origin, who from 1897 to 1914 designed many residential buildings in the city. Boublík also headed the Czech Conversation Club (Česká beseda) in Lviv – the oldest Czech association in the world outside the original Czech lands – where he was also an amateur actor and director. The activities of Karel Boublík assumed an important place in the artistic life of Lviv at the end of the 19th and the beginning of the 20th century; consequently, it is important and urgent not only for the study of the architecture of the city to research, preserve and popularize the heritage of this artist. His personality and work have not yet been examined in detail in the intentions of art history and in his homeland, in the Czech Republic, Boublík is still unknown among experts.

The purpose of the article is to uncover and define the specifics of Boublík’s architectural legacy. The study is based on a comprehensive approach, using biographical and historical-cultural methods, including artistic analysis. Archival sources and information from the press at the time are an integral part of the study.

Boublík’s buildings are an example of the stylistic transition from Historicism in its Neo-Baroque version to Art Nouveau and the second wave of Historicism in 1909 – 1914, with elements of modernized historical styles. His buildings were exceptional in their originality, with a special emphasis on sculptural decoration and metal ornaments. The architect’s tendency to highlight protruding spherical and prismatic forms has been demonstrated, with a sharp vertical accent of roofs, often pyramidal, with complex ends – with multi-level wavy and rounded attics, towers and dormers.

The Chamber of Commerce and Industry in Košice

The year 2020 saw the 90th anniversary of the construction of the Chamber of Commerce and Industry building in Košice, as well as the 125th anniversary of the birth of its designer, the Košice architect Ľudovít Oelschläger. These commemorations lead us to consider the fate of this remarkable multifunctional structure, a listed cultural monument and important example of Košice modernism, which has long ceased to serve its original purpose and now lies empty and neglected. Indeed, the latest owner was able to reclassify the building as residential and is currently selling the property. Its forlorn state and uncertain future use, together with the impending deterioration of its still-present architectural qualities, warn of the potential threat both to the physical integrity of this cultural monument and its expressive originality.

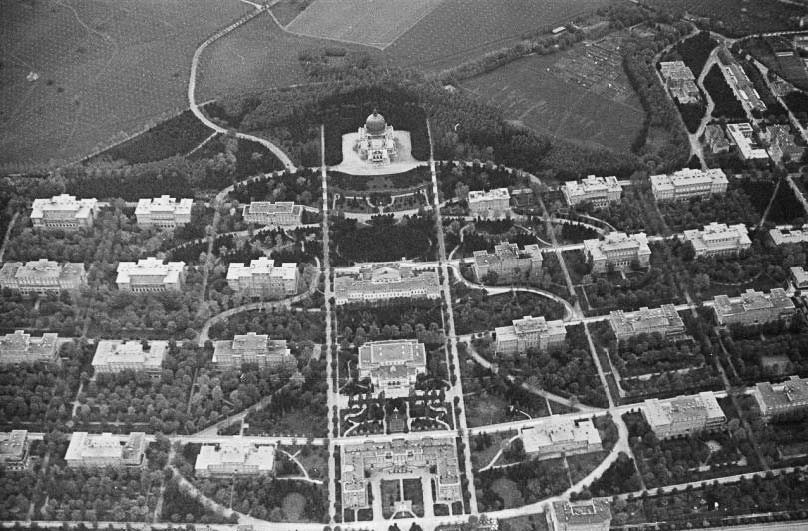

Heritage, Culture and Regeneration of the Former Military Areas in the City of Oradea, Romania

There are places where history is still alive: heritage sites, locations of great cultural, scientific, educational, and social significance. The military presence in the city of Oradea, Romania, generated an impressive cultural-historical heritage, both tangible and intangible, as the consequence of centuries of alternative militarization and demilitarization processes. The aim of the article is to explain that the former military areas are great sustainable historical, cultural, architectural and socio-economic local assets, with a specific function in the urban texture. The research methodology combines a review of the relevant literature, fieldwork, analysis of the evolution and status of the former military areas, and synthesis to help reach our conclusions. The results of the study underline the great significance and role of the former military sites in the urban structure, society and economy, by providing important functions like tourism, education, public administration, military, residential, commerce or industry. The main issue is the transformation of the abandoned military heritage sites into potential elements of sustainable urban development to create a new and vivid part of urban texture. Built heritage of former military areas is found across many countries and this article explain the particular common features, helping sharing experiences, know-how, best practices on the transformation of military sites to public uses in Europe and around the world.

Tito’s Villas in Herceg Novi – Regional Contexts and State Residences

Considering the growth trends of cities within specific regional contexts, the focus of this paper is the contemporary architecture of the bay of Boka Kotorska, a World Heritage region protected by UNESCO. The youngest and largest town is Herceg Novi located at the entrance of the bay. Against the attractive setting of the coastal and inland landscape, its dynamic cultural and historical context directly shapes the formulation of the architectural environment, which cannot be reduced simply to the set of formal relations with the local site.

The main research subject of this paper is the architectural discourse from the last decades of the 20th century as well as the perspective of physical architecture, through the research optics of analysis of this specific region. Its focal point consists of two architects which were among the most significant practitioners in this area and involved in the key urban definitions of Herceg Novi in the second half of the 20th century. The review is given with special reference to two state residences, villas built for Josip Broz Tito in Herceg Novi: Villa Galeb and Villa Lovćenka. The nature and architectural scope of these buildings is identified, the concept design methodology is examined, predominantly in decoding the relations with relevant influential factors, not excluding the highly specific socio-political context.

The general goal of this paper is to specify the character and the scope of the work and authors who implemented a clear and discernable design approach at the end of the 20th century in Herceg Novi. The state residencies built for Josip Broz Tito in this town have not been the subject of critical research so far. As such, they have provided a worthwhile case study for the identification of design methods in the creation of impressions on the representatives of state power and their role in urban landscape of a coastal town. A secondary goal of this paper is additional accumulation of knowledge on the relevant architectural history of the Adriatic coast, as well as highlighting the significance of an architecture displaying evident regional qualities.

Zdeněk Řihák’s Hotel Buildings and the State Project Institute of Trade Brno

The text briefly describes the operation of one of the state planning establishments for hotel construction in Czechoslovakia from 1960 to 1990, placing the architectural work of SPITB employee Zdeněk Řihák within the global context of that time. The Czechoslovak hotel production and the work of Zdeňek Řihák is analysed on for case studies: Hotel Continental in Brno (1961 – 1964), hotel Panorama in Nové Štrbské Pleso (1967 – 1970), Labská bouda in the Krkonoše mountains (1969 – 1972) and hotel Patria in Štrbské Pleso (1969 – 1973). Zdeněk Řihák and his generation of architects had a great influence upon the development of Czechoslovak architecture. Unfortunately, their works are now disappearing due to a lack of understanding or to free up land for developers. In most cases, however, these are valuable buildings whose rights to existence and heritage conservation have not yet been adequately exercised, so that not even Řihák’s hotels are safe from inappropriate alterations and impending demolition. Fortunately, visitors can nonetheless still admire the best-preserved examples of Hotel Patria at Štrbské Pleso and Hotel Continental in Brno, whereas Labská bouda and the Panorama now appear worse off….

Socialist Industrialization as a Factor of Urban Development and a Difficult Legacy in Košice, Slovakia

The postwar decades were significant for urban development in Central and Eastern Europe since many cities grew rapidly and were industrialized. The Slovak city of Košice illustrates how industrial entities’ localization catalyzes urban development. The development in the years after 1945 changed the city character from middle size provincial town into a large industrial city. Later, the post-socialist transformation redirected this trend and left postindustrial areas within the city structure. From a path dependency perspective, the first phases of socialist and post-socialist periods show similar dynamics as a time of significant changes that set the guidelines for city development.

The City as a Place Prepared for Neurodiversity

This study aims to analyse and reflect on the relationship between architecture and human neurodiversity. Individuals with different cognitive capabilities perceive and use space and it’s elements differently. Despite the fact that modern medicine has positively contributed toward and shift in social paradigm towards mental health and its impairments, the level of stigmatisation in the society is still relatively high, and very obvious in the European countries. A target group study examines architectural typology of psychiatric institutions of hospitals, sanatoria and social services establishments in Europe, with an emphasis on the historical context. Through the topic of care for people with mental health impairments it demonstrates the dynamic development of the role that architecture plays in relation to social interaction.

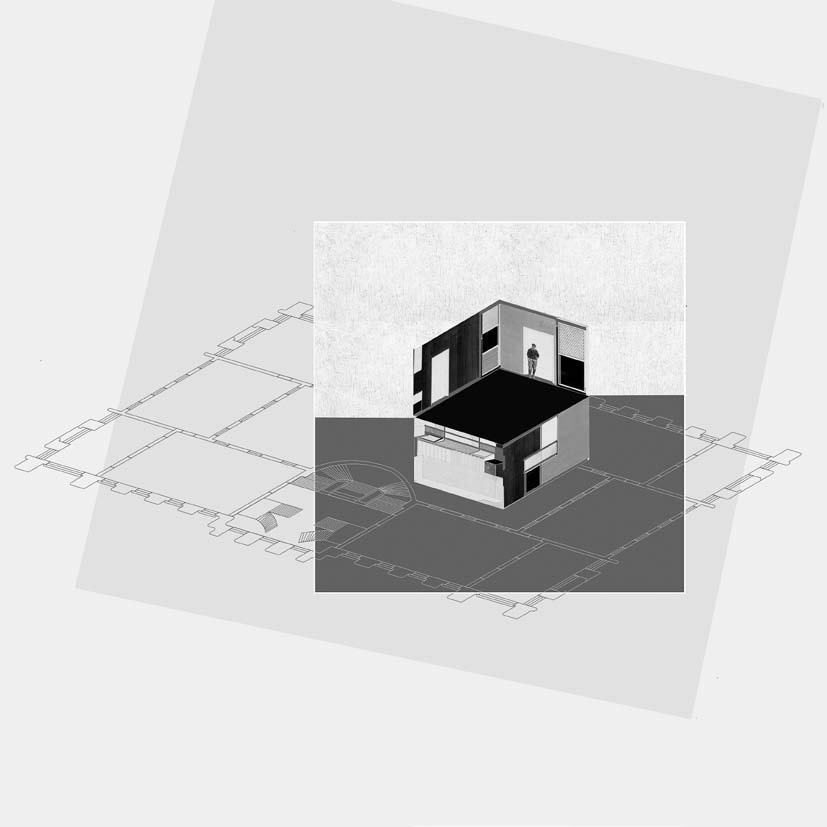

The Experiential Museum – Avant-Garde Spatial Experiments and the Reorganization of the Human Sensorium

Avant-garde artistic experiments are unquestionably recognized as relevant to the museum field in the context of art and museum studies. This paper aims to reconfirm their relevance in the architectural context as well, selecting crucial cases and protagonists whose final products were not artworks or exhibitions per se, but new (concepts of) space. These new concepts of space were all treated as democratic and participatory new media capable of training and modernizing the whole of our human sensorium. In this way, a curious partnership is discovered between this “experiential” art museum and the discourse on architectural modernity. Imaginary space, expressionist space, correlational space, multimedia space and situationist space – these are the principal categories that this paper recognizes as five distinct productive devices for modernist perceptual reorganization.

Export/Import of Modern Town

Planning Principles

Urban planning of the 20th century, especially in countries under authoritarian regimes, has left behind significant traces in the urban environment as well as in the countriesʼ landscapes. It was a turbulent period when the policies of often-shifting political orders could easily change from one day to the next, along with the preferred approaches of urban planning and development, while at the same time the efforts towards technocratic progress and national development clashed (often aggressively) against local customs and traditions.

The aim of this thematic issue is to point out the parallels and, at the same time, the differences or peculiarities of the results of modern urban planning in different regions, with an emphasis on identifying the influences highlighting local and regional (urban, state and national) impacts that have translated into specific reflections of global modernity. The topic is discussed across several layers – from the definition of the basic principles and differences of the systems of developing and developed countries, the identification of the role of “exported” impacts on local specifics and, of course, the role that education influences the further careers of architects and urban planners. In the context of the Central European region, the topic of “export” of this specific local approach on architectural and urban design in other countries is still little known and neglected in research. However, it was Eastern Bloc countries that encouraged the participation of their engineers, architects, and other technical staff in the preparation of various construction projects in the transforming post-colonial regions, especially in Central Asia and Africa. The export of project work lay fully within the intent of “strengthening the importance of international coordination of the management of the economies of socialist countries”. This cooperation was regarded as an aid to developing countries, but also spread the reputation of socialist architecture, technology and its politics. …

Our book of Bauhaus

MARKÉTA SVOBODOVÁ BAUHAUS A ČESKOSLOVENSKO 1919 – 1938 STUDENTI / KONCEPTY / KONTAKTY

Praha, Kant 2016. 256 p.

ISBN 978-80-7437-224-7

Industrial heritage (of Bratislava) through various views

NINA BARTOŠOVÁ, KATARÍNA HABERLANDOVÁ: INDUSTRIÁL OČAMI ODBORNÍKOV/PAMÄTNÍKOV Teória a metodológia ochrany priemyselného dedičstva v kontexte Bratislavy

Bratislava, Vydavateľstvo STU 2016. 128 p.

ISBN 978-80-227-4658-8

Assigned to architecture

KLÍMA , PETR (ed.): RŮŽENA ŽERTOVÁ: ARCHITEKTKA DOMŮ I VĚCÍ

Praha, Vysoká škola umělecko-průmyslová v Praze 2016. 280 p.

ISBN 978-80-86863-87-0

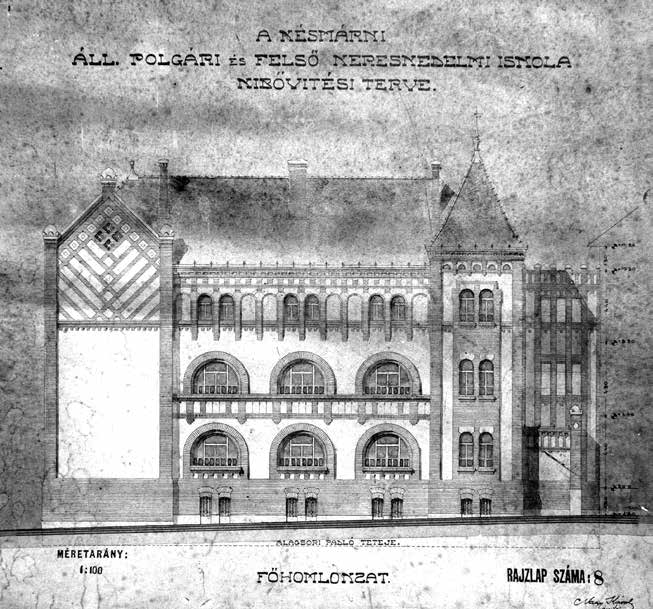

The Addition to the Kežmarok State Boys’ School and Commercial Academy

An extensive process of school building at the turn of the 19th and 20th century occurred in tandem with the development of the educational system within the Austro-Hungarian Empire. Beside increasing the level of education, the state aimed to achieve the transformation of the multilingual multiethnic Hungarian Kingdom into a homogenous, unified Hungarian nation. By the early 20th century, there also began to appear attempts to apply the Hungarian national style to the architecture of school buildings, as we can now see even today in Kežmarok.

When the building of The addition to the Kežmarok state boys’ school and commercial academy proved insufficient to match the growing number of students, the Ministry of Religious Affairs and Public Education issued a decision to add a new section to the existing building. Károly Nagy, Jr. (1870 – 1939), a Budapest architect, developed the project in March 1913.

Following the project’s approval, the ministry announced a tender for construction works, which eventually reached a cost of almost 160,000 crowns. Kornél Bittsánszky, a building contractor from Žilina, submitted the lowest offer. Other companies from Budapest and Kežmarok participated in the work as subcontractors. Construction began on September 15, 1913 and the planned date of its completion was set for the beginning of August 1914.

The addition was joined to the existing building through an interconnection section parallel to the northern wing of the older part of the school; the addition protrudes ahead of the old one in the direction of the newly-formed street, or more precisely in the direction of the park situated behind the castle. It has an irregular rectangular ground plan with a spatial arrangement where the configuration of particular rooms conformed to the modernistic doctrines stressing the importance and primary purpose of the rooms as well as their orientation toward the cardinal points. The arrangement of rooms in the building is considered quite innovative for the era. Unlike the usual classical two-aisle building with a series of classrooms facing the street and the corridor section facing the courtyard, the new school provides a striking counter- example. Presumably, such an unusual arrangement was due to different light and temperature conditions: the classrooms are oriented to the greater sunlight of the south and east side and the corridor to the north side. …

Lotte Stam-Beese (1903 – 1988) From Entwurfsarchitektin to Urban-planning Architect

The paper takes a closer look at the career of the Silesian-born urban-planning architect Lotte Stam-Beese. This female architect became famous not only in the Netherlands, but also in the circles associated with CIAM, for her designs for modern post-war housing districts in the city of Rotterdam. An initial basis for Stam-Beese’s career was laid in the thirties when she worked at Bohuslav Fuchs’s architectural firm in Brno. The author also focuses on her work at this firm and her other activities in Czechoslovakia. The article is based on various sources consulted in archives in the Czech Republic, Germany, Ukraine, the United States and the Netherlands.

Industrial Heritage Utilization

A specific modernist building typology, namely the transformer stations that arose with the introduction and spread of electric power usage in the first half of the 20th century, forms the topic for examination in this paper from the architectural and urban-planning points of view. In addition to providing research on this developing period in Budapest, the architectural approach is complemented with a number of urban-planning-related issues. As a consequence of the power grid development, the utilization of historically and architecturally valuable monuments of the industry left vacant through disuse has also become essential. Therefore, beyond the usual historical approach, the issue of rehabilitation and utilization arises as a new interpretive horizon, taking international examples into account.