The conception of the “welfare state” on the most generalised level can be understood as the state-generated system of social institutions that implement policies for the protection and support of economic and social well-being respectively a definite living standard for the citizens. In the ideal model, the welfare state should be grounded in principles of equal opportunities fair division of resources, and public responsibilitiesfor those who, for whatever reason, are incapable of securing for themselves a dignified life. In the differing regions of Europe, the definition and the form of the welfare state had its specific traits, conditioned primarily through divergences in the historic development of the social policies of individual states. The most telling different, though, is manifested in comparing the post-socialist lands of Central and Southeast Europe with those of liberal or social-democratic regimes, whether within Europe or indeed elsewhere.

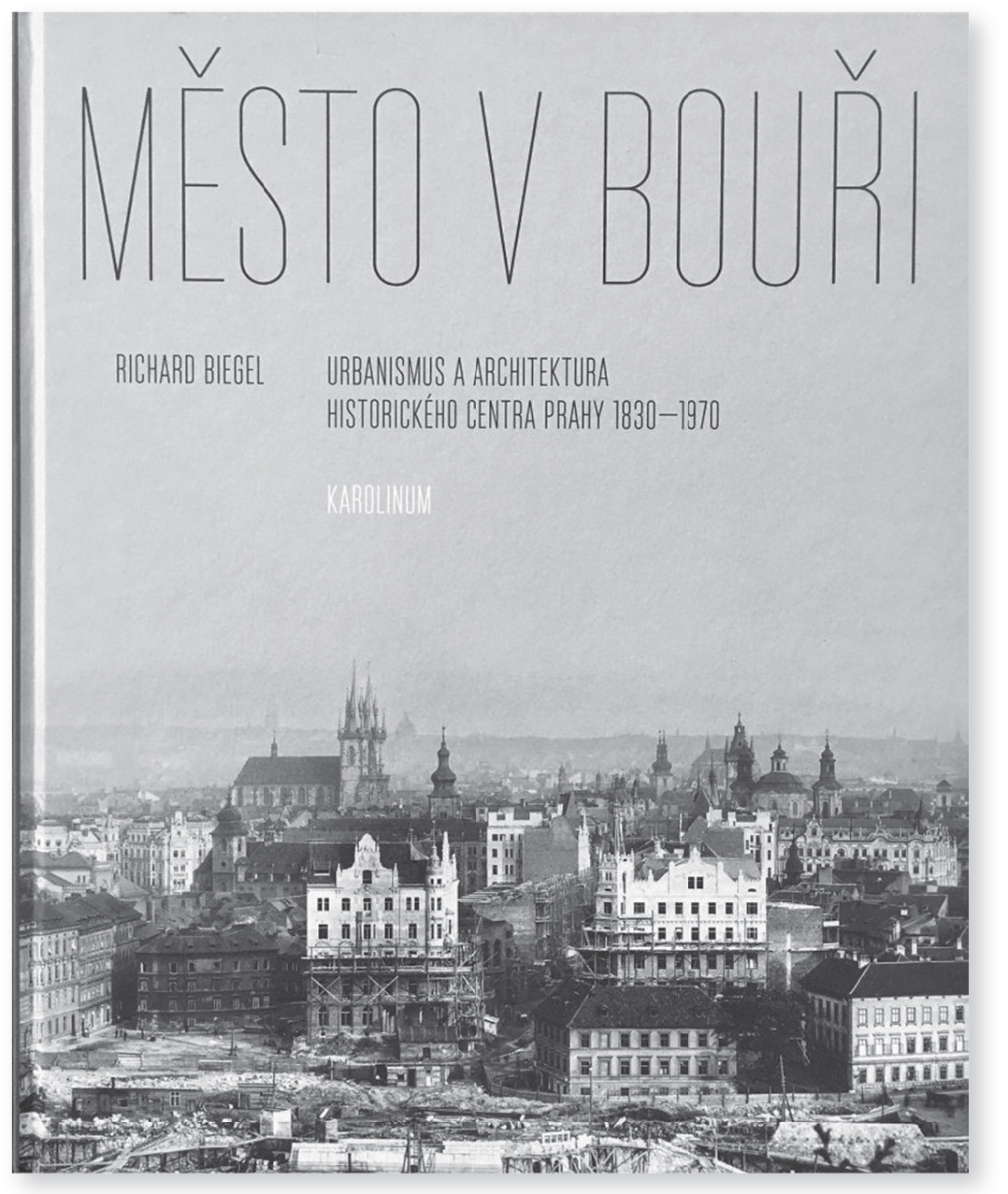

Architectural and urban design was regarded from the mid-19th century onward as a vital tool for the realisation of particular projects leading to improvement in the social situation of the populace, above all addressing the negative consequences of rapid industrialisation. Investigation of models for deling with social problems throughout history and their reflections in architecture and urbanism has become a vital task precisely in such a situation of social instability and economic crisis as we must confront today. The resilience of social state and non-state support systems is now being tested the most severely since the end of World War II.

The urgency of the need to investigate the mutual influences between social policies and architectural-urban solutions in modern history is confirmed by the enthusiastic response the present journal has received to its present theme, From Philanthropy to the Welfare State: The Influence of European Social Policies on Architectural Design and Urban Planning in the 19th and 20th Centuries. Likewise, the intellectual potential of this question is revealed by the broad diversity of views, or respectively methodologies, through which the researchers have approached it. With the aim of following historical development, the contributions have been ranked in thematic-chronological succession, in which the most frequently addressed themes are social housing, health care, urban planning, and work with the public space.

Indeed, these focus on aforementioned topics should come as no surprise, since these are, after all, the areas of architecture that rank, in terms of securing the social and health needs of the public, among the most central ones and directly influence the quality of life for large strata of society. At the same time, these matters are all closely linked, as became clear already by the 19th century, when the Industrial Revolution launched massive migration of rural populations to cities. The resulting housing crisis opened public discussions on the ways to ensure financially accessible and hygienically acceptable housing, not only in industrial centres. Greater demands for hygiene, in turn, were themselves determined by the development of health care and medical treatment, linked to reflections on the construction of new modern concepts for the architecture of hospitals and sanatoriums. At the same time, the trend for constructing medical or social facilities only responded to the era’s massive spread of infectious diseases, in particular tuberculosis. It is this question that is addressed in the present issue by Jana Pohaničová and Matúš Kiaček using the examples of selected realisations of health-care buildings in Slovakia in the period after World War I, the work of three authors: architect Michal Milan Harminc, his son Milan Anton Pavol Harminc, and builder Rudolf Emanuel Frič. In the area of social or health-care facilities, another focus of interest is projects intended for orphaned or otherwise socially or medically disadvantaged children. All modern political regimes turned targeted attention towards social measures to support children, regarded as the “future of the nation”. Brigita Tranavičiūtė, in her study, discusses how the inter-war state of Lithuania assumed the role of protector of children’s health in the decades between the 1920s and the early 1940s. Through creation of the physical infrastructure in the form of a network of children’s summer camps, in her view, allowed children’s health and recreation to reach a new level of quality.

The greatest challenge in programs of social assistance, though, has long remained and still is that of accessible and adequate housing. Though certain of the first designs of modern social housing from the 19th and early 20th centuries took the form of idealistic utopian visions, the motivation of those who built housing for their employees was hardly that of mere philanthropy. At least an equally strong motivation was the desire of employers to ensure for themselves sufficiently numerous, healthy, productive, and loyal work forces. Realising projects of social housing, derived from architectural plans for a higher housing standard and ambitious urban proposals hoping to create entire complexes with shared amenities and green areas, nonetheless often turned out to be problematic. In their articles, Martin Jemelka, Laura Umbrai, and Ágnes Nagy describe how the planned standards for dwellings, public facilities, and urbanistic designs in fact were often weakened during realisation because of limited financial resources or equally the economic aims of construction entrepreneurs or developers. And the employers building housing, who rightfully deserve the title of pioneers in social housing’s history, built apartment blocks or entire neighbourhoods not only for their regular workers, but also for the upper levels of their employees, such as engineers, managers, or even members of the company’s directorates. As these authors all stress, it was hardly exceptional for the inhabitants of the progressively designed residential complexes, originally intended for production-line workers in manufacturing (the “workers’ colonies”), more often to be higher-qualified employees with regular salaries, since being less threatened by market instabilities they would be able to pay higher rents. For this reason, many workers’ families living in more modern housing variants with higher standards preferred to reduce their living standard by taking in boarders or subtenants who would cover part of the rent cost. And thus, the sad reality for the greater part of industrial workers thus remained that of mass shelters, unhealthily damp cellar flats, or self-built dwellings in informal settlements on the urban periphery.

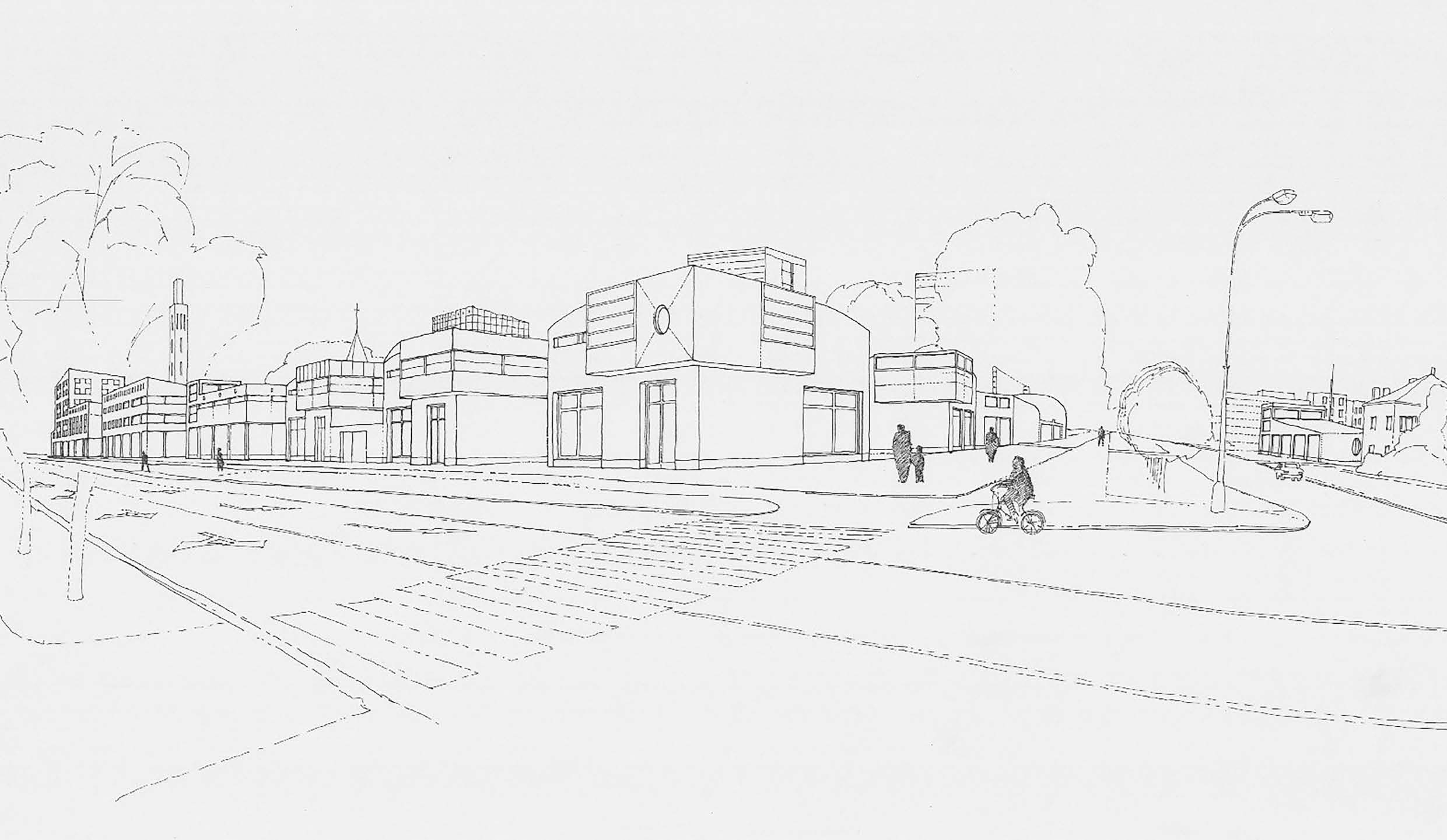

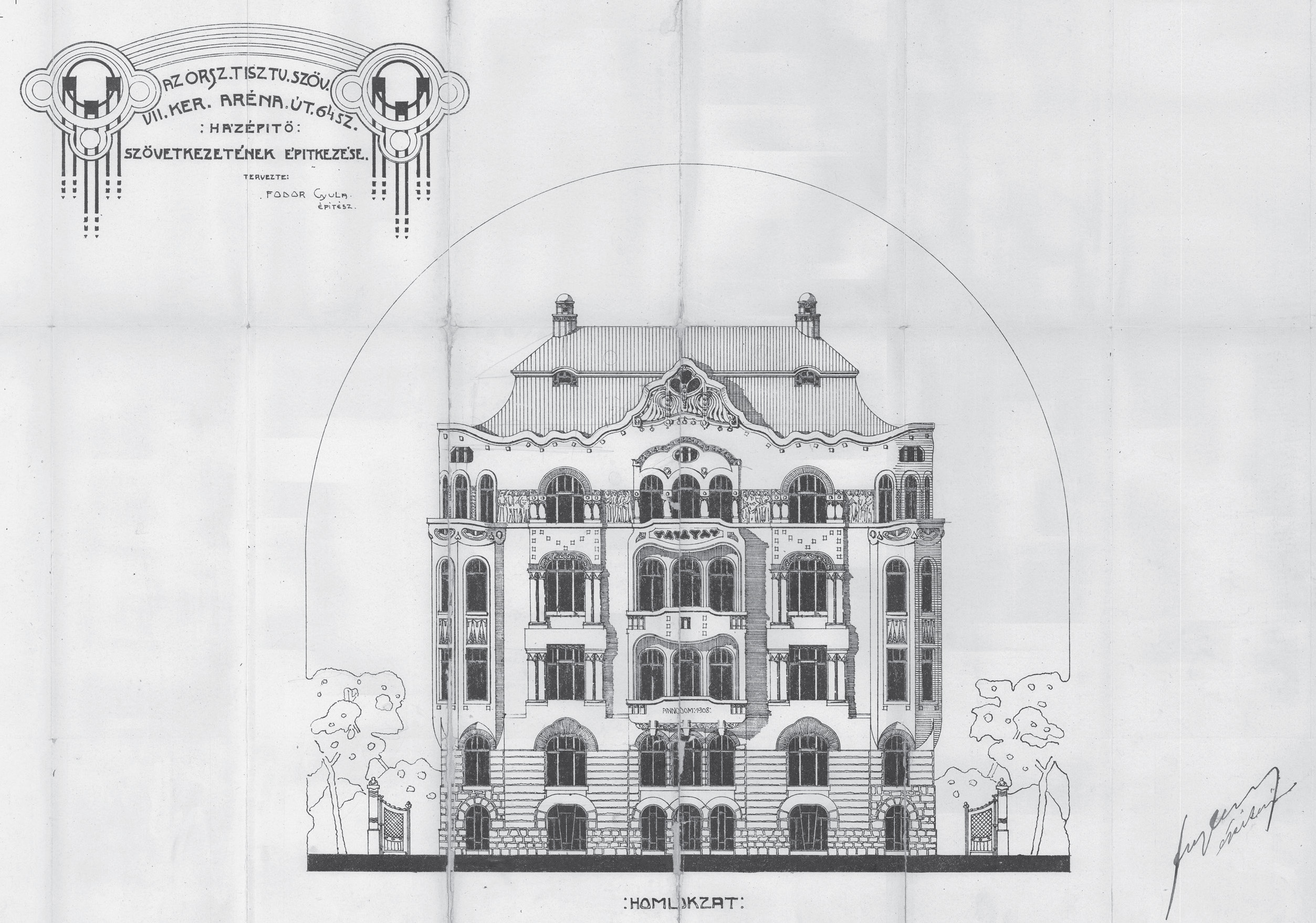

For this reason, it is worthwhile, and not only in terms of architectural or urban history, to examine the unrealised aspects of the plans, as well as the question of what social group truly received the social housing. Yet the housing shortage in cities lay no less heavy on the middle classes. Many examples from the past illustrate that social housing was frequently not accessible to those groups in society most in need, but to those better situated who could pay for the regular housing costs. Related to this circumstance is the question of what forms of investment and property ownership turned out to be best suited to the construction and maintenance of the social housing created. Models of social housing where the units were planned for gradual transfer to the personal ownership of the inhabitants were, initially, rare. Self-help cooperatives for constructing small flats emerged as an attractive alternative, which grew significantly in the years after World War I.

Though the form of the housing cooperative was recommended even for constructing housing for the most impoverished, the initial capital and the financing necessary for building maintenance significantly limited the number of the future inhabitants and co-owners. Cooperative apartment construction and ownership, as a result, emerged as the domain of lower- to higher-middle-class urban dwellers. The results of research focusing on the founding of cooperative and their operation, as well as analysis of the legislation that regulated this construction method through the 20th century in the former Czechoslovakia have been presented in this issue by two authors. Katarína Haberlandová analyses the example of a single specific housing cooperative, which at the start of the 1930s built several apartment buildings, of which one – Avion, intended to house middle-class residents – belongs among the most successful concepts of cooperative housing in interwar Bratislava. The reason lies not only in its architectural qualities but equally in the model of financing its operation, which partially covered the expenditures for other buildings in the cooperative inhabited by significantly poorer tenants, who in the years of the Great Depression struggled more intensely with unemployment than middle-class ones. Marta Edith Holečková examines the question of cooperative housing in the 1959–1970 period from the wider perspective of political events, in which cooperative construction re-emerged in the post-war era in the context of the new socialist regime in Czechoslovakia and its legislation. Her focus is on housing construction in Prague.

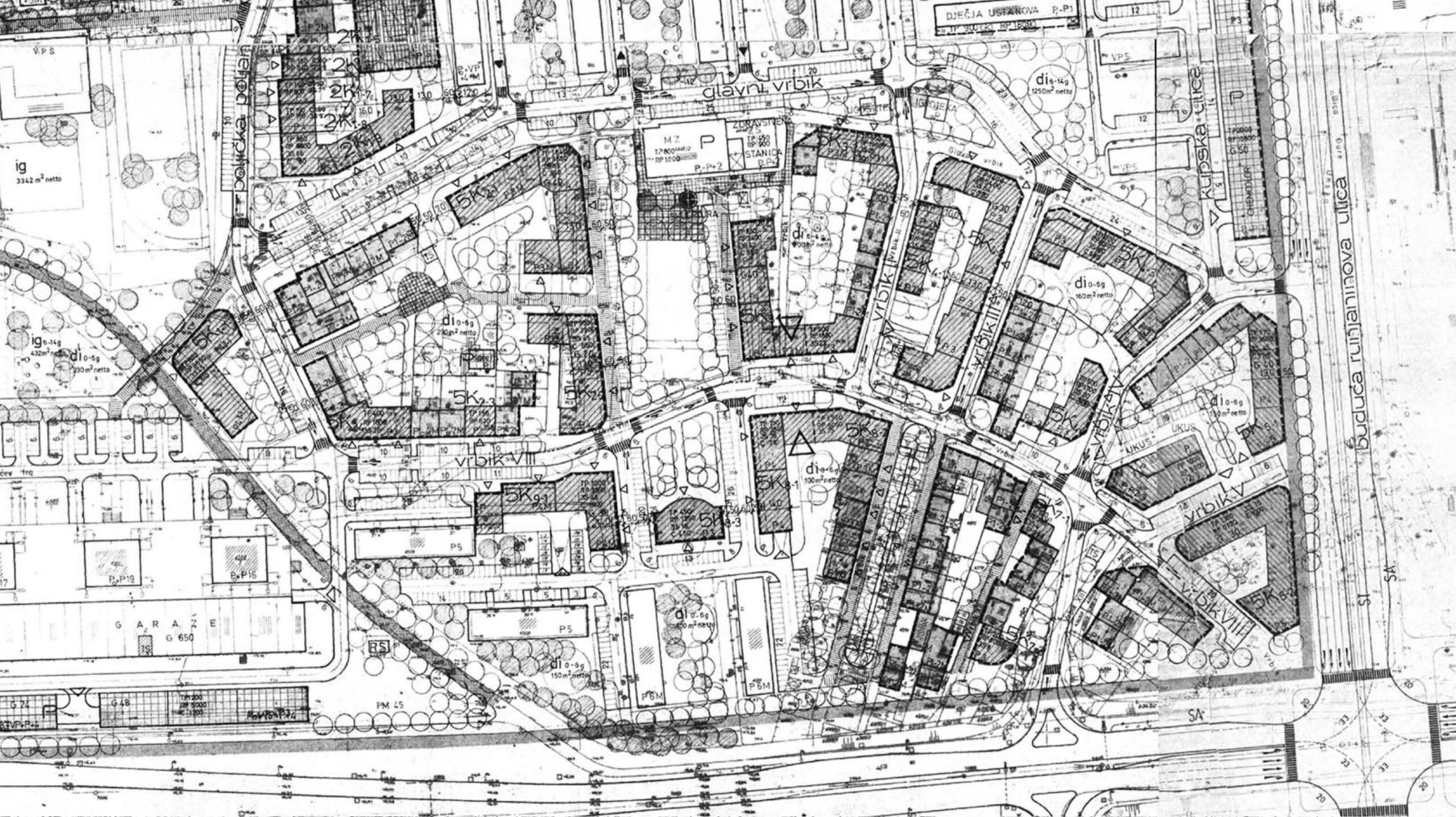

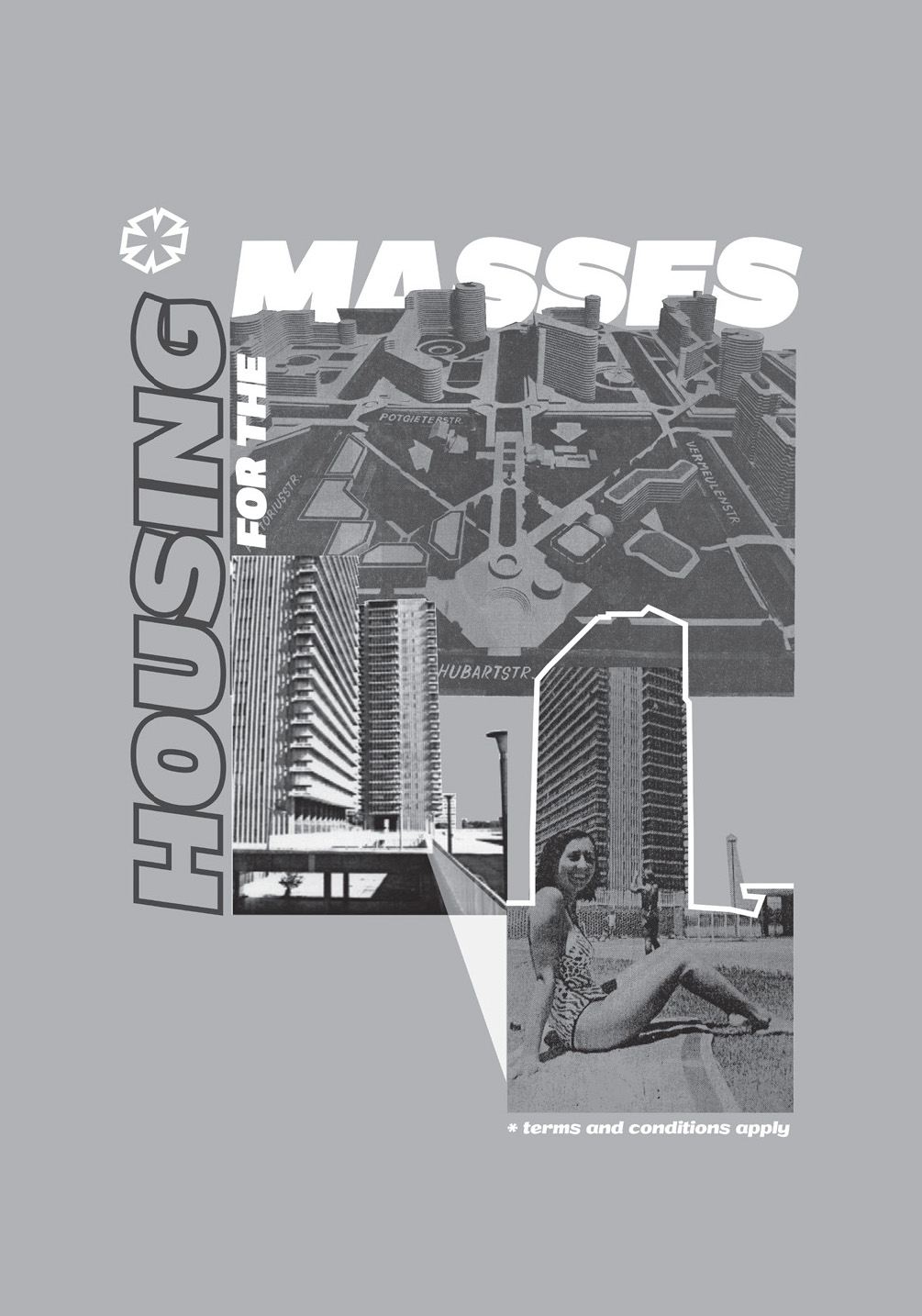

The need to increase the pace of construction for hew housing led, by the end of the 1950s, to the expansion of prefabricated concrete-panel methods, which achieved the true sense of the word “mass-scale” primarily in the socialist bloc. In this part of Europe, new flats in prefabricated housing estates became the general standard for middle-class or even upper-middle-class strata in urban areas, while in western Europe this housing typology remained confined to the lowest classes, consigned to social aid from state or local authorities. One intriguing and evidently typical trait for Europe’s post-socialist states today is a combined type of ownership for these prefabricated apartments. Ágnes Nagy, in her study on housing construction in Budapest, explains how this currently dominant hybrid form of ownership, the condominium – in which the owner of flat is a private individual, but the remaining parts of the building are in the property of the owners’ association – developed out of the original cooperative forms that expanded in the interwar years. She adds that the primary reason lay in the desire of tenants to own their own dwelling, even if it was merely one unit in a shared apartment block.

Following the contributions mapping the situation in central Europe, it is exceptionally interesting to make a comparison with the results of research outside of this region and the socialist bloc in general, presented by Ana Tostoes and Zara Fereiro. In their study on the concepts of social housing realised in Lisbon in the 1960s and 1970s, these authors present five housing categories differentiated by architectural designs, specifically chosen for different social classes. No less inspiring, in this vein, are the texts published in the section Forum, which provide an image of European colonial influence in the area of social housing on the African continent. Cornelius van der Westhuizen focuses on projects realised during the post-war urban renewal of Pretoria in South Africa, strongly marked by British legislation and concepts of the welfare state. Yasmine Nour El Houda Saidi and Najet Mouaziz Bouchentouf, in turn, characterise the predominantly French influences on the construction of social housing in the 1950s in the Algerian industrial city of Tlemcen.

Indeed, the process of following the historical trajectory of models of state social assistance in housing against the backdrop of the various political regimes and ideologies of Europe in the 20th century forms the connecting line for the present thematic issue of the journal. Comparison of examples and contexts aptly reveals the mutual influences and the specific differences between individual European regions. Today, as we face our current crisis in a unified Europe, we are confronted with social problems in the framework of the neoliberal system, calling for greater application of the right of the public to participate in shaping the city. In addition, many previously realised projects – not only housing but also in other areas such as culture, health care, or education – represent through their undeniable architectural and urban qualities a vital cultural layer of the city with strong heritage value, requiring sensitive revitalisation. Cities need to be viewed holistically, as a complex historical and cultural-social testimony, no less influencing their current life. Such reflections emerge in the contribution by Jasna Gailer investigating the historical context of the evolution of the urban form of the small Istrian mining town of Arsia (now Raša in Croatia), begun in Mussolini’s Italy in the 1930s, and on this era’s debate on architecture and urbanism as it oscillated between modernity and tradition. In the case study of this town, the author sheds light on the complexity and contradiction of its architectonic culture from 1930s up until the post-socialist transition.

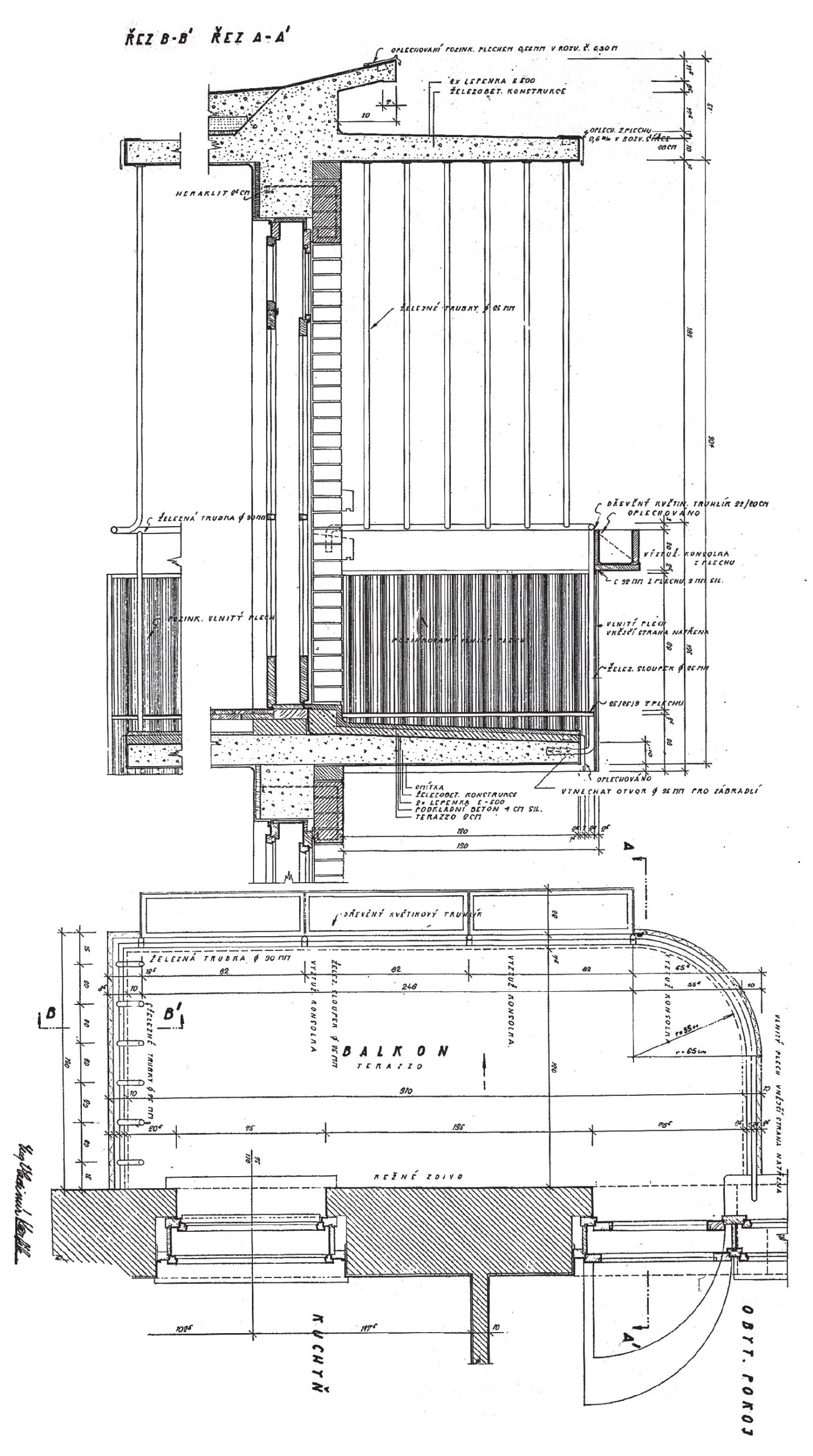

The range of contributions to the current issue presents a spectrum of innovative approaches supporting an interdisciplinary view, generating intriguing methodological overlaps between architectural, urbanist, historical, social-historical, or ethnological research, even involving use of the techniques of oral history. Completing this mosaic of methodological standpoints is the paper by Nina Bartošová, involving a theoretical analysis of the architectural element of the balcony as a symbol of democratisation in modern society, where this theme is illustrated through the social housing designed in the 1940s in Zlín by Vladimír Karfík. As we have already noted, for many authors it was important to reflect the current situation facing concepts of social construction from the 19th and 20th centuries. Martin Jemelka offers an original typology of complexes of social housing, not only for company employees, which could serve as an instrument for further comparisons in a wider historical and geographic scope. Various types of social housing from the past could also be confronted with the architectural, urbanistic, or construction methods in use now, a comparison that, among other results, has the potential to become highly useful in the critical formulation for projects of social construction in the future.