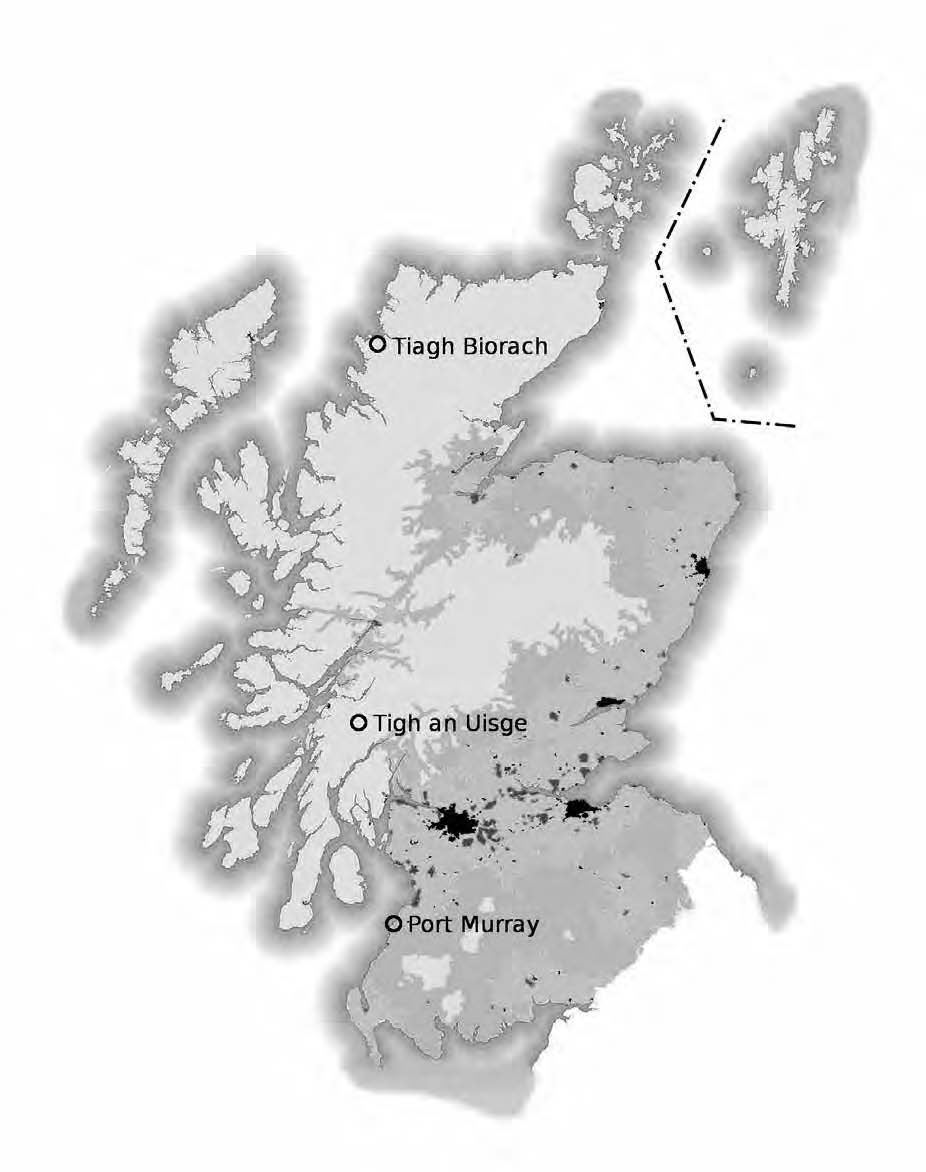

Whilst Scotland’s postwar urban planning and mass housing are well documented, the historiography of mid-20th century architecture consists otherwise of relatively few monographs on renowned architects. The history of architect-designed houses is insufficiently researched, despite the existence several outstanding buildings scattered across the country. This paper discusses three such Modernist houses, erected between 1959 – 1963 at seaside locations in remote Scotland, and reflects on how their remoteness influences their upkeep and use. All designed by well-known architects, the houses are Port Murray by Peter Womersley (recently demolished), Tigh an Uisge by Morris & Steedman and Tiagh Biorach by John Hardie Glover.

Author: Dagmar Slámová

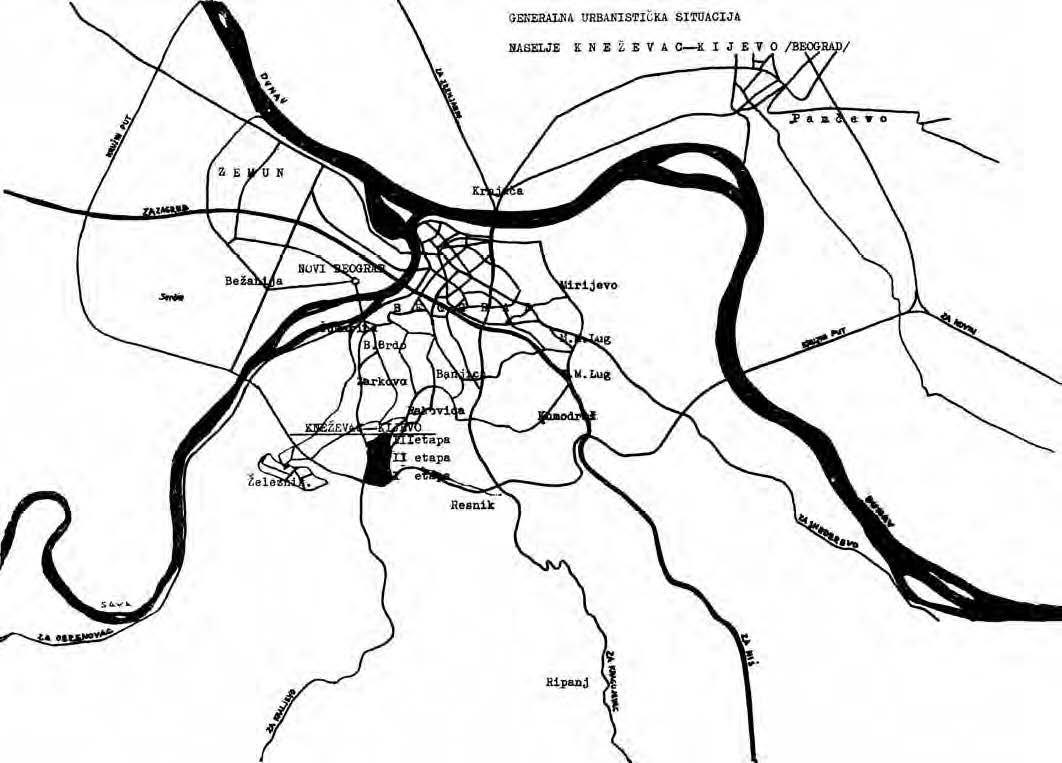

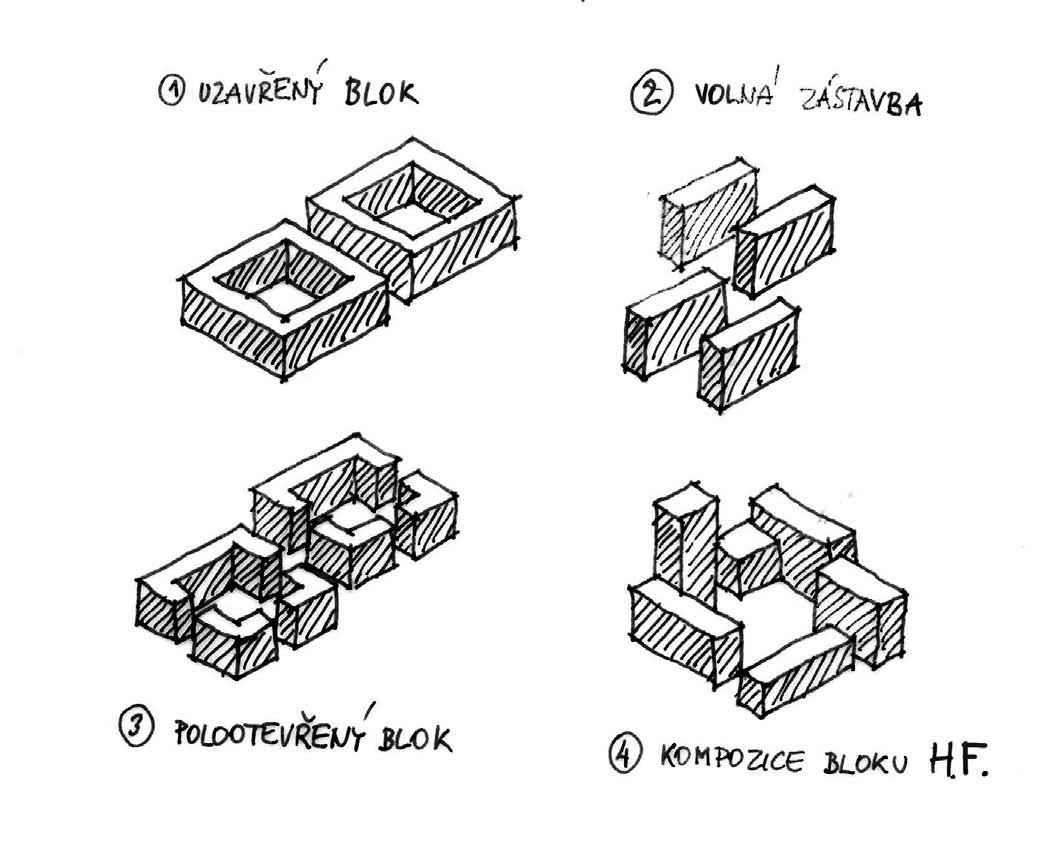

The Problem of the House in 1960s Belgrade: Mediating the Individual and the Collective

Focusing on the architecture and ambience of the low-rise high-density single-family housing estate Petlovo Brdo in Belgrade, Serbia (1967 – 1969), the article relates the everyday social production of space in socialism as a modernist-vernacular fusion of the notions of the folkloric and the peripheral. The socio-spatial balance between the individual and the communal, as attempted by the estate’s architects Elsa and Branislav Milenković, is achieved by variation of seven apartment types in four block types and their diverse grouping in immediate neighbourhoods with pedestrian circulation. The architectural design supports modular coordination, apartments use-value as a function of layout disposition, environmental mindfulness and an aesthetic of domesticity and small-scale urbanity.

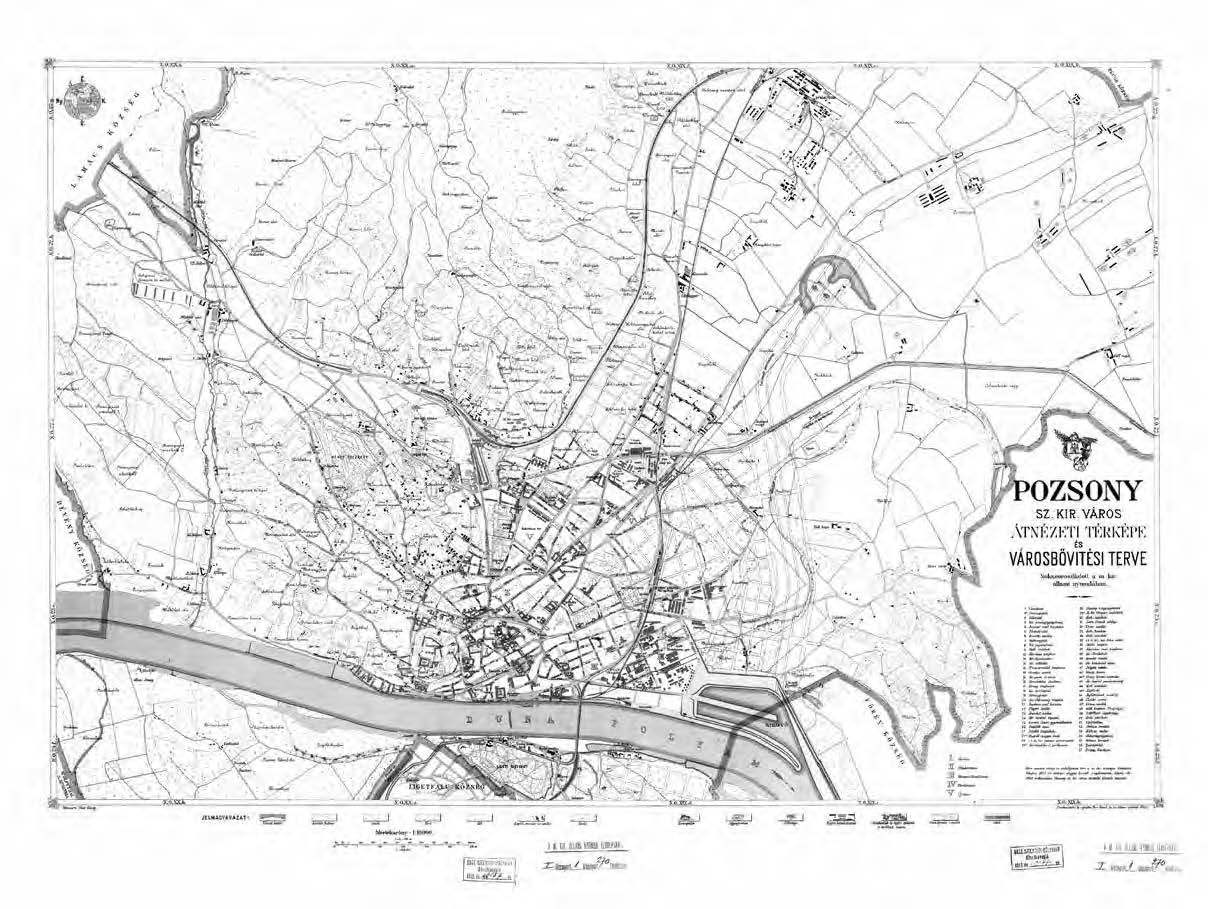

Red or Blue? The Start of Modern Planning in Bratislava

This study presents the history of modern urban planning in Bratislava (then Pozsony/Pressburg) at the turn of the 19th and 20th centuries. It identifies the first three plans for regulation and enlargement of the city: the plan by the City Technical Division from 1898 through 1906, the plan of the retired construction commissioner of Hungarian State Railways Viktora Bernárdt from 1905 and the plan of the Budapest architect and urban designer Professor Antal Palóczi from 1907 to 1917. The study analyses the plans in terms of their principles of city formation, which at the time was the leading principle in urban-planning discussions. Within the process of analysis, though, we also make reference to their local perception as captured in the era’s print media – which forms one of the main sources of information for the present study.

Changes of Town Centres in the Era of State Socialism – Processes and Paradigms in Urban Design

Approaches towards town centres in various eras are highly revealing of the contemporary way of thinking and the pervasive ideas about the past and the future. During the state socialist era, the standpoint was highly unstable, constantly changing according to major shifts in economic and social politics throughout the 45-year life of the regime. These changes left their marks on urban design as well, a state especially conspicuous in medium-sized towns and their centres. This paper deals with these processes in town centres, as well as their underlying causes and their impact on urban policies, urban design and architecture. While the details of processes and examples focus on Hungary, they have strong connections to other Central-Eastern European countries as well, due to the many presumable similarities.

Where is French Urban Design Headed? The Involvement of Private Investors in the Plannning and Implementation of Large-scale Urban Development Projects

The article focuses on the transformation of organization of French large scale projects under the progresive liberalization of urban development policies. The transformation of approaches to real estate investment and the reposition of hierarchy of its main actors evolves towards new methods of large scale project management. This influences the urban form, whose new model is so-called macroblock. Three large scale urban projects Paris-Rive-Gauche, Lyon Confluence a Île-Seguin – Rives de Seine in Boulogne-Billancourt are used for illustration.

Swiss Academic Professionalism and Czech Academic Activism

Texty o architektuře 2014 – 2015: Švýcarsko – české inspirace

Texts about architecture 2014 – 2015: Swiss – czech inspirations

Praha, Kruh 2015. 192 p.

ISBN 978-80-903218-6-1

„Urban Public Space“ as Auditorium and Stage – its Stability and Transformations

Petr Kratochvíl: Městský veřejný prostor

Praha, Zlatý rez 2015. 188 p.

ISBN 978-80-88033-00-4

Leaning Against Architecture

Emancipated: first generation of women architects in Slovakia, exhibition

Emancipované: prvá generácia architektiek na Slovensku, výstava

Foyer FA STU, 8. decembra 2015 – 15. januára 2016

Kurátorka výstavy: Henrieta Moravcíková, fotografie: Olja Triaška Stefanovic, výtvarné riešenie: Laura Pastoreková, architektonické riešenie: Martin Zaicek

Výstavu podporili: Ministerstvo kultúry SR, Fakulta architektúry STU, Oddelenie architektúry ÚSTARCH SAV

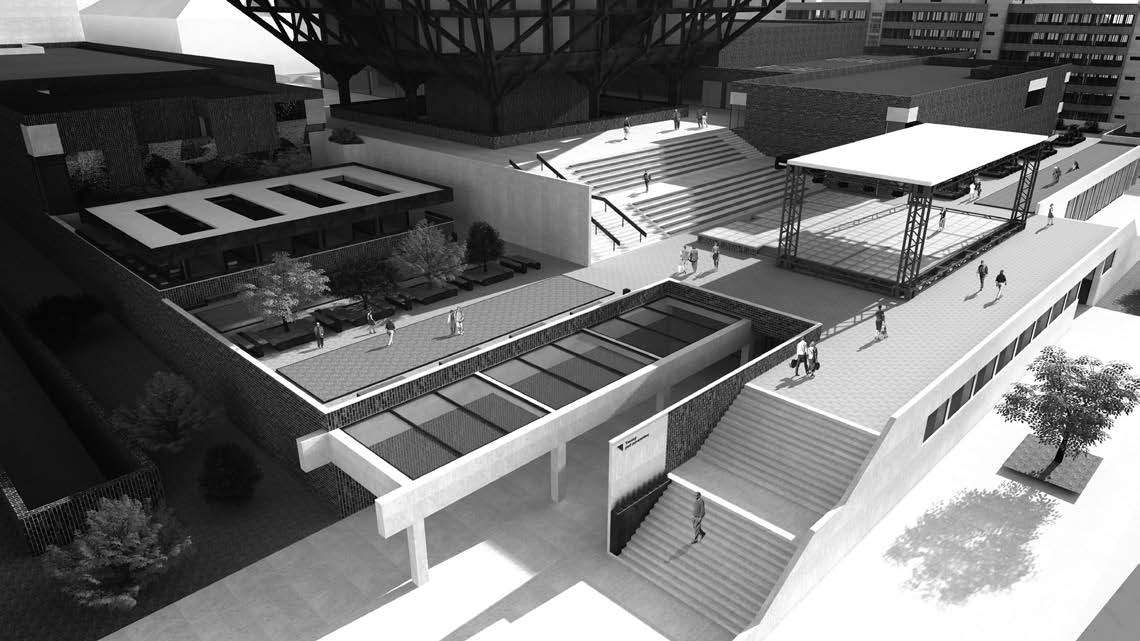

Revitalisation of the Roof Terraces of the Slovak Radio Building: A Contribution to the Improvement of its Image

- Since its completion, the Slovak Radio Building has been struggling with notable unpopularity; however, the situation is now changing. Responsibility for this shift has been due to the actions of Slovak Radio and Television (RTVS). In cooperation with the Faculty of Architecture of the Slovak Technical University (STU) and the Department of Architecture at ÚSTARCH SAS, RTVS has established in the premises of the Slovak Radio building an educational path “preco pyramída” [Why a Pyramid], presenting the greatest attractions and uniqueness of the Slovak Radio Building. Since its opening, the Radio Building’s educational path has been visited by a large number of visitors. This circumstance has significantly improved the image of the building. Until the end of 2015, the activities of the civil association “Jedlé mesto” [Edible City] also contributed to improving the image of the building through the creation of a community garden on the building’s open terraces that had not been in use for 30 years. Although this project did not fully succeed, it focused attention on the potential of these spaces (the terrace). This has stimulated RTVS to the decision to reconstruct and continue to use the roof terrace space for public activities.The basic idea of the proposal of the reconstruction of the roof terrace was the aim to preserve their social life by integrating functions and services otherwise absent in this part of the city. In this way, the original concept of the terrace, only as a space to be passed through, would be changed and the terrace would itself become a destination point. All suggested interventions adhere to the original proposal, and also respect the principle of reversibility while not damaging or in any way interfering with the existing elements of the Slovak Radio Building.

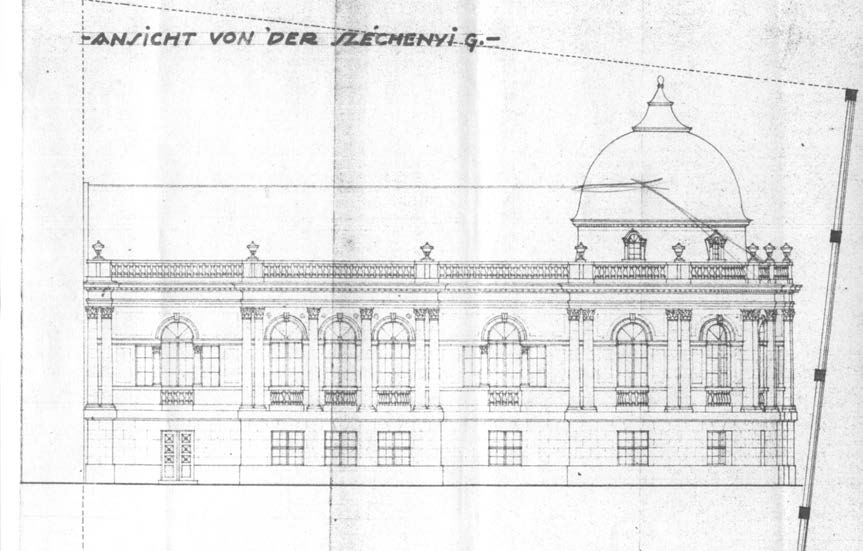

Notes on the Bratislava Activities of the Architect Emil Brüll´s Construction Company

The architect Emil Brüll was a member of the group of Slovakia’s Jewish architects who died or were executed during WW II. He worked in Bratislava, mostly in the 1920s and 1930s. This contribution aims to clarify and complete our information about his work. Many buildings that have been the subject of study for architecture of the interwar period have been ascribed authorship by Brüll. However, according to the findings of our research he worked on these buildings only as a builder. The inaccuracy was caused by the marking of project documentation, archived as a part of the permission to use the building and examined by researchers, with the stamp “Architect Emil Brüll, building enterprises”.Despite Brüll´s widespread building activity in Bratislava during the First Republic, we know very little about his personal life. He was born in 1891 in Bratislava, into a Jewish family. He began his university studies in 1909 at the Royal Hungarian Technical University of Archduke Josef in Budapest, also called the Polytechnic. In spring 1922, after his graduation, Emil Brüll returned to Bratislava and established a firm in partnership with Emanuel Lebovics. On February 1923, they designed and constructed a twostorey building in Grösslingová ulica 55. The project documentation is signed in both German and Hungarian, “ArchitektIngenieur, Emil Brüll & Emanuel Lebovics, épitészmérnök”; a small marble tablet on the house facade reads in German: “Entwurf u. Ausführung, Brüll und Lebovics, Architekten u. Baumeister”. At present, this building is the only realised architectural design known for which clear authorship can be ascribed to to Brüll and his partner Lebovics. The search for an original form architectural expression underway in the early twenties is legible in this building, as well as in the buildings of most of the region’s postwar architects.Regardless of the exact range and authorship of Brüll´s own architectonic work, the activity of his building company led to the highquality realisation of works by many wellknown architects of the era, which we can admire even now in nearly unchanged form. According to facts as currently established, Brüll cooperated with the major architects of functionalism, mainly in the period of the thirties, the most important years of his firm. Among those architects were Alexander Skutecký, Július Sporzon and Ludovít Korínek, H. K. Stark, or Bohuslav Fuchs. Brüll also specialized in complex assignments, e. g. multistorey apartment blocks with at roofs, buildings with reinforced concrete structures, or foundations laid in complicated geological conditions. His realizations were often impressive buildings that fully represented the aesthetic hopes of the era and the social status of their clients. Currently, the activities of Brüll’s firm in Bratislava’s central zone and its rapidly developing suburbs have largely been recorded. The present study would like to open for discussion the topic of a more detailed understanding of architect Emil Brüll´s work. His activity in Poprad, Slovakia, where he reportedly stayed from the beginning of WW II, and where he is believed to have designed the airport and several private residences, remains unknown.

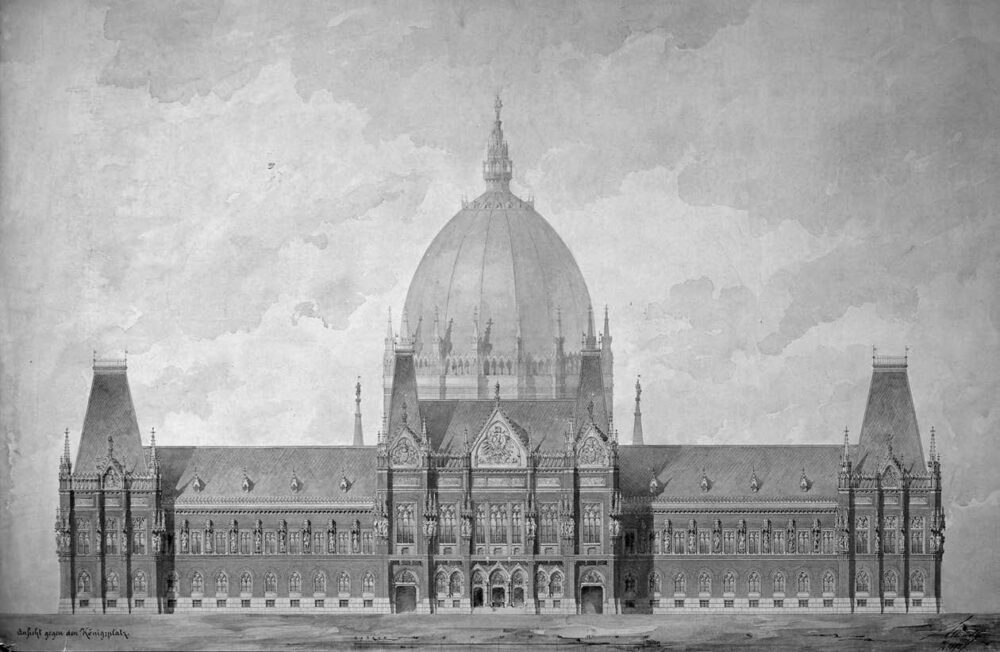

Imre Steindl’s Neo-Gothic Approach in the Hungarian Design Competitions of the 1870st

Introduction

The Plan Collection and Archives of the Department of History of Architecture and Monuments at the Budapest Technical University possesses many valuable drawings and photographs, including several documents related to Imre Steindl. The most signi€cant pieces of Steindl’s are the fourteen sheets of the Reichstag proposal plan of 1872, and a folder of original photos presenting his plans, in this case consisting of planvariations of the Budapest City Hall. The Reichstag plans were first published by Alice Horvath in 1988. Her paper appeared in German in the Periodica Polytechnika Architecture, and one year later also in Hungarian in the Muvészettörténeti Értesíto. One sheet of the Reichstag plans was displayed at the exhibition in the Museum of Fine Arts (Budapest) in 2000. A brief description was also added to this plan in the exhibition catalog. Jozsef Sisa’s book on Steindl gives a short description of the Reichstag planseries – based mainly on the paper by Alice Horvath. …

Depiction of the “Industrial World” in the Architecture of Interwar Prague

The prominent German conservationist Axel Föhl, whose work focuses on industrial heritage, organized a section at the XIV Congress TICCIH in Freiberg in 2009 which, for the first time in the history of these congresses, dealt with the issue of how the arts (painting, sculpture, graphics, photography, film, literature) responded to the phenomenon of the industrial revolution and how the arts (particularly architectural sculpture) made a connection with the most highly industrial and technical architecture, as well to other typological categories of buildings. The interdisciplinary meetings were attended by historians of art and architecture, architects, museum workers and conservationists. The results were published in an anthology, later in 2013 in a monothematic number of the magazine Eselsohren (Art and the Industrial Revolution), in 2015 in an enlarged and supplemented Czech publication Industrial Buildings and the Arts (FÖHL, Axel – POPELOVÁ, Lenka (eds.), BOLLEREY, Franziska – SKREBSKÁ, Renata – KARLSTREMA, Inga – VIAENE, Patrick – ABILDGAAR, Hanne – GLAVOCIC, Daina. Industriál a_umení. Praha, CVUT 2015).The relationship between art and industry has been studied so far mainly in a connection with the visual arts. Even in the publication Industrial Buildings and the Arts, half of the contributions dealt with artistic manifestations, while the remainder concerned the interpretation of sculptural expressions on the theme of industry (as well as trade, finance and agriculture) for industrial and technical buildings, but also other typological ones. In this regard, the research target is unique. Although one of the most interesting aspects of industrial heritage, and one pointed out by such authors as Betsy Hunter Bradley (The Works: The Industrial Architecture of the United States, 1998) and Peter Navarson and Merlin Palmer (Industrial Archaeology, 2000), that topic has not been devoted sufficient attention. Only Gillian Darely has dealt completely with the description of the visual codes in industrial architecture in the book Factory, and at the same time he has emphasized their relation to social utopias of the era.Industrial heritage, as defined by the Charter for Industrial Heritage, consists of all the remains of the industrial culture which have a historical, technological, social, scientific or architectural value. Hence, the field of exploration necessarily includes the depiction of industrial processes and technologies, and the question of the aestheticisation of the industrial and technical buildings. By studying of these artistic expressions, information can be gained not only regarding the historical development of architecture and engineering, but also the development of processes and technologies (often already extinct), social and economic phenomena, lifestyle, etc. …

Late Modernism in the Slovak Spa Localities

Though small in size, Slovakia is rich in its springs of natural healing water. These springs are an important precondition for the development of the spa as a social institution, yet natural resources alone cannot provide all the services of a spa. For the providing of therapy, what is necessary is a complex of balneology and sanatoriums, which together with the natural surroundings create the spa environment. In the second half of the 20th century, Slovak spa localities were the setting for massive construction development, intended to improve Slovakia’s spas to the level of the best world quality. As a consequence, we can observe here several dozen complexes of realized objects, build in the aesthetics of late modernist architecture, most of which are still in use in the original form and provide a crucial part of the spa services in Slovakia. The spa development from the period of the 1960s to the 1980s was both a €nancially and technically complicated process, organized by the centralized spa organization Slovakoterma Bratislava, a state enterprise forming an important partner to the design institute Zdravoprojekt, itself responsible for the design of most of the realized post war concepts in Slovak spa localities.In 1948, political power in Czechoslovakia was seized by the Communist Party. In the same year, new legislation was introduced by which all natural resources, including natural springs, were nationalized. All spa localities become the part of the company Czechoslovak State Spas and Springs. In the following years, the spa locality was described by the new legislation as a place for health rehabilitation. For the €rst time, Slovak spas became a part of the institutionalized curative – prevention health care system. In addition, shortly before the communist revolution, in 1947 a special balneological congress was held in Štrbské Pleso in the High Tatras, where it was decided to divide all approximately 50 Slovak spa localities into categories of importance and indication groups. According to this plan, 3¨categories were created: 1. spa of international importance, 2. spa of national importance and 3. spa of local importance. Only the spas of Categories I and II received further development as part of the curative health system.Up until the 1960s, there was no new construction development, though all former spa hotel facilities were reconstructed into a hospital type of accommodation in the process called “dehotelization” of the spa.During this time the new legislative background and institutions of the control and management of the spa were created as well. …

Deformations of the Vacationscape. The Mechanism of Changing Effects on the Balaton landscape after 1968

BBalaton’s waves brought consolidation in even wider circles” – this quote from the famous lyrics of a song entitled “The Sixties” confirms that the development of the largest lake in CentralEurope had a pivotal role in the social policies intended to reestablish the socialist system in Hungary after the 1956 revolution. In parallel with the social consolidation after 1956, the starting development of the holiday resort opened a unique professional opportunity for architects to deal with regionalscale development alongside regional architecture in the frame of the centralised state system, although the most intensive development phase began only after 1968, in changing political conditions. The quoted text, in fact, expresses the highly ambiguous situation of the period, offering restricted freedom in the framework of socialism, and refers to the different and ambivalent memories in which the common subject is the extended development program around the lake, notonly in the wider public but among architects as well.The development started at the end of the fifties, at the same time as the end of the socialistrealist era, in other words the years during which modern architecture became legitimate. Young architects appearing on the scene after the war faced limited resources, technologies and finances at the beginning of the Balaton development, yet the relaxation of ideological pressure gave them the possibility of inventive formal solutions. A later member of Team X, Károly / Charles Polónyi, the Chief Planner of the south shore, presented the first results as a regional path towards modernism at the Congres Internationaux d’Architecture Moderne (CIAM) in Otterloo in 1959 and six years later these plans won the Union Internationale des Architectes (UIA) Abercrombie Prize.In spite of the prestigious awards achieved by the first phase of the realization, the broader architectural legacy of the Regional Plan and the current situation of the buildings reveal a far more debatable picture. Brie y put, the heterogeneous architectural quality resulting from the long realisation times and the damage to the natural landscape dating from this period, do not re ect the initial planning ideas. …

The vision of the socialist city on the example of Nová Ostrava

Nová Ostrava, later called Ostrava-Poruba, is the most notable example of a new industrial city founded and constructed in the period of early socialism in Czechoslovakia after World War II. The particular mode of architectural forms, which is strongly evident in the plans of the new city and significantly affected its initial part constructed between 1951 – 1956, was already, at the time of its creation, known Socialist Realism. The architecture of Czechoslovakia in the first half of the 1950s has still not been clearly evaluated and accepted, even though it has already become in some cases the subject of heritage conservation. Contradictory views are also encountered in the scholarly evaluation of Socialist Realism, and its inclusion in the development of Czechoslovak and European architecture from the beginning of this debate post1989. As an important industrial hub of Czechoslovakia, the city of Ostrava was significantly damaged by military action at the end of World War II. After the war, it was necessary to repair and complete the missing ats quickly, yet also to replace the substandard housing in the workers’ colonies of many industrial plants. Gradually, the spontaneous construction of residential houses in the vicinity of factories gave way to strict construction plans of housing estates located outside the polluted industrial environment and coal reserves. This trend, based on the functionalist foundations laid out in the Athens Charter, eventually prevailed and established the requirement for a clear separation of housing from heavy industry. For decades now, this trend has shaped the face of the city, addressing part of the city’s problems at the time of construction yet also generating new problems to be faced by today’s generation. The first completed construction of new ats located according to plan in appropriate locations of the city was represented by the Model Housing Estate Belský les, where work began in 1946. The housing estate was supposed to be built within a two-year plan and serve as a model for other housing estate projects. Its concept was derived from the prewar tradition of functionalist urban planning and the specific architectural design of individual buildings. After 1950, the amount of construction was limited and the design projects for additional buildings were already in uenced by Socialist Historicism. …

Stratigraphy of the Smart City Concept

The paradigm of the city is now undergoing substantial change against a background of economic, technological and social transformations caused by globalization. The traditional postindustrial city is to be replaced by the city characterized by such attributes as green, sustainable, open, rational, ecological, ideal, creative, global, and generic… – and the notion of Smart City is the overarching summation of all of these characteristics. Bearing in mind that the English adjective smart is replaced in Slovak by the equivalent intelligent, the question remains whether an inanimate entity (like the city in the traditional thinking) can be intelligent. That is, if we define intelligent as possessing or displaying the ability to learn or understand things, or to deal with new or difficult situations. No precise definition of the Smart City concept can be said yet to exist. Perhaps the most useful statement might define it as a district, urban fragment, and ultimately an entire city which is energy efficient, which saves resources, produces minimum emissions, and provides the highest quality of life for its residents. The basis is a wellfunctioning infrastructure at all network levels.According to the authors of this article, the concept of the Smart City can be divided into several distinct layers (strata). This layering / stratification is evaluated by a series of vertical sections, aiming to analyse the interplay, overlaps and in uences, mostly on urban society. Does thinking about the Smart City concept really start at the edge of the town, or rather within its environmental and economic substructures? Is it possible to speak of the “smart region” or even “smart country”? The authors present the selected layers and their essential characteristics, the impact on the lives of people and on the environment.Smart information technologiesAt present, it is generally admitted that the concept of the Smart City is based on ideas taken from information technology and data acquisition (“real-time information”). In that regard, one can use terms such as “wired city” or “digital city”. ….

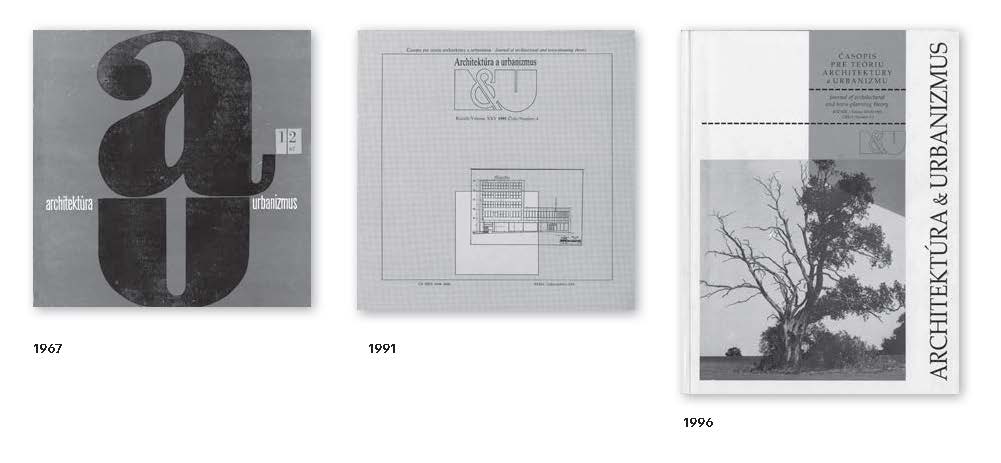

Editorial

The decade of the 1960s was an exceptionally favourable one for the Czechoslovak cultural and intellectual world. It was during this time that a great many noteworthy initiatives arose across all areas of social life – and the scholarly sphere was no exception. The era’s overall enthusiasm, the emergence of new research trajectories and the desire to present the results achieved at the highest possible level were re ected, specifically, in the founding of the € rst scholarly journal treating architectural design and urban planning in Czechoslovakia.Architektúra_& urbanizmus, journal of architectural and townplanning theory, to give its full title, was created in 1967 with its institutional base in the institute of Construction and Architecture of the Slovak Academy of Sciences in Bratislava, working in cooperation with the Department for the Theory ofArchitecture and Creation of Living Space of the Czechoslovak Academy of Sciences in Prague. At its founding, the journal was not only notable for its content alone – but no less for its form. The author of the original graphic design of the journal was the Slovak artists Tatiana Križanová Lizon. Its square format and strikingly coloured cover, with the area occupied by the initials “a” and “u” in lowercase form, were a characteristic product of the Sixties. The hypertrophied icon ‘au’, layered one above the other, remained the recognisable logo of the journal for over twenty years. A change in layout only occurred in 1991, with the new graphic format and the journal logo, now in the form of a stylised ‘A&U’, designed by architect Peter Moravcík. While the actual logo then persisted up until 2015, the cover design and internal typographic organisation changed twice in the intervening years: in 1993 in the design of graphic designer Jany Sapáková and in 2009 from the plan of art historian Peter Szalay. As such, the design of the journal closely re ected not only its internal dynamics, but also broader social circumstances. And the tradition of high artistic cultivation in the journal has continued up to today, to our re ections on how to visualise its € ftieth anniversary issue. As a result, for the € rst time in the history of A&U, its form has become the subject of an artistic competition. This competition took place in two rounds in late 2014 and early 2015, and attracted several leading representatives of Slovak design: Juraj Blaško, Anna JablonowskaHoly, Matúš Lelovský, Peter Liška, Boris Meluš and Lubica Segecová. The jurors, Marcel Bencík, Lubica Hustá, Henrieta Moravcíková, Mária Rišková and¨Peter Szalay, eventually entrusted the design of the journal to the hands of designer and instructor at the Bratislava Academy of Applied Arts Juraj Blaško. Hence the journal will now appear in a new form, one continuing the high visual level of the periodical, developing its potential, and while retaining continuity with the past moving the publication itself visually into the 21st century.

Michal Milan Harminc – Pragmatist of Two Centuries

Jana Pohaničová – Matúš Dulla: Michal Milan Harminc. Architekt dvoch storočí

Bratislava, Trio publishing 2014. 184 p.

ISBN 978-80-8170-003-3

Understanding the Urban Heritage – Morphogenesis of the Traditional Urban Blocks

Körner Zsuzsa A történeti városszövet megújulása 1870 és 1940 között

Zsuzsa Körner Renewal of the Historic Urban Fabric between 1870 and 1940

BME Urbanisztika Tanszék, Budapest, Hungary, 2015, 183 p.

ISBN 978-963-313-146-6

Disasters in the Histories of Towns Destruction or a New Beginning?

Pohromy, katastrofy a nešťastia v dejinách našich miest

18. – 20. október 2016

Slovenská historická spoločnosti pri SAV –Sekcia pre dejiny miest

Joyfull Architecture ?

Care (Sorge) for Architecture: As king the Arché of Architecture to Dance

Kurrators: Benjamín Brádňanský, Petr Hájek, Vít Halada, Ján Studený, Marian Zervan, in cooperation wit the exhibition commisioner Monika Mitášová

May 28th – November 27th 2016

Pavilion of Czech republic and Slovak republic, 15th International Architecture Exhibition, Venice

Towards the Future of Modern Movement Architecture

14th International Docomomo Conference

Adaptive Reuse Modern Movement Towards the Furture

Lisbon, 6. – 9. September 2016

A Recollection of the Department of Architectural Theory

The ‘Department of Architectural Theory and Creation of the Living Environment’ of the Czechoslovak Academy of Sciences (ČSAV) was founded in 1964. In the spirit of the then-pervasive political programme of the Communist state, it was intended to use scientific means to develop methods towards the creation of an ideal architectonic and natural environment for the citizens of the socialist state. In turn, these findings were to have served the organs of the state as guidelines in the shaping of programs concerning the given question. The department was formed by a ‘multidisciplinary team’, compiled from various professions – architecture, sociology, psychology, medicine, agronomy etc. In addition, it coordinated the research investigations of other institutions that addressed similar questions. In the exciting period of the later 1960s, it was fully engaged in the ‘renewal process’ leading to the Prague Spring, and played host to passionate discussions – yet all this ended with the Soviet occupation in August 1968. In 1972, the Department was dissolved, and its environmental section transferred to the Institute of Landscape Architecture of the ČSAV, with the other (primarily architects) shifted to the Institute for Philosophy and Sociology. Here, if under a different name, the traditions of the pre-1968 Department remained preserved, along with an increase in cooperation with the Slovak Academy of Sciences in the newly founded journal A+U. The majority of research publications, from within the Department or outside, collected in the Department’s library over a single decade, were deliberately destroyed after it was moved to new quarters. The Department was a true product of the time, and in the 1960s it formed an excellent discussion club. No less interesting were the people who guided it, the erudite architect Zdeněk Lakomý and the socialist idealist-pragmatist Otakar Nový, who was the official reviewer for recent domestic work. The remnants of the Department, with overwhelmingly new personnel, were then placed in 1986 under the Institute of Art History of the ČSAV, as the architecture division.

The Conference ‘On the Scientific Problems of Architecture’ in 1958 and Its Possible Recapitulating, Generating and Modelling Lines

The study addresses the importance of the third scholarly conference organised in the 1950s by ÚSTARCH SAV under the title On the Scientific Problems of Architecture. The initiator of the conference was academician Emil Belluš, who invited important Czech and Slovak architects as well as art historians. The conference was divided into two thematic blocks addressing these questions: 1) What is architecture under socialism?, 2) What are the tasks of science in architecture? The text is a theoretical analysis of the basic concepts in these two blocks. At the centre of attention are the conceptualisations of architecture and the ideas of socialist architecture, science of architecture, and science in architecture. The important of the conference lay in its three underlying trajectories: recapitulation, generation and modelling. The first finding shows that the meanings and definitory procedures were not merely a result of the era’s demands, but retained many traditions of the (primarily) Czech interwar avant-garde. Secondly, it is shown that within the discussions themselves, there emerged new modifications of meaning and new intellectual forms. Thirdly, the paper reveals what the conference could provide as a potential model for the future.

Architectural Meanings and Their Mode of Reference – Analysis Through Publications

The aim of this paper was to undertake an analysis of the modes of reference of architectural meanings. For the purpose of the analysis, categories of meanings are defined relying on the work of Nelson Goodman and Erwin Panofsky. The proposed method was tested on the example of two buildings: the Yugoslav pavilion at EXPO ’58 and the Pavle Beljanski Memorial Collection. Selected publications about buildings were analyzed and the main idea of the examination and systematization of meanings through their mode of reference was elucidated through the given examples, so as to ensure it is applicable for other buildings.

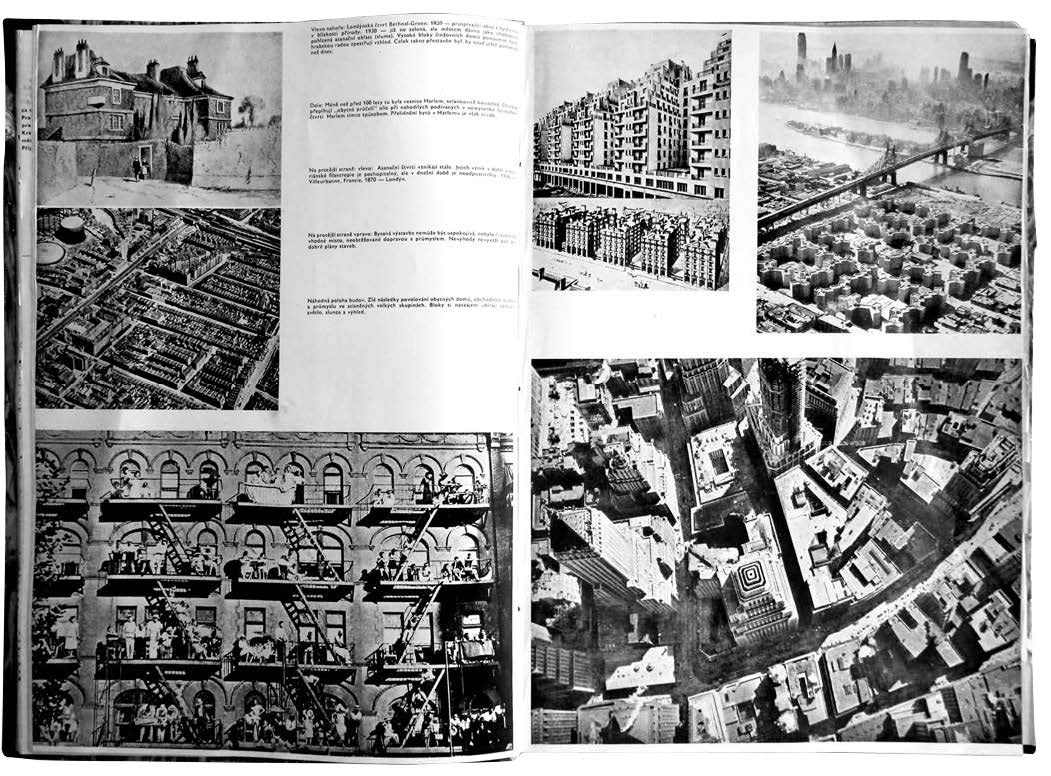

Osmosis or Propaganda? Western Urbanism in Czechoslovak Architectural Press (1945 – 1960)

The article investigates the representation of Western (West-European and Amer¬ican) urban planning in the professional architectural press in Czechoslovakia during the turbulent period of the early years of the communist regime in 1945 – 1960. Focusing on media discourse, the study discusses the transfer of architectural and urban design concepts within postwar Europe and ques¬tions the assumption of the dominant position of Soviet ideology in urban planning and the degree of isolation of Czechoslovak urbanism. Investigating the concepts of publishing architecture, propaganda, and Soviet perception of internationalization, this analysis studies the osmotic access of Western influences through the semipermeable membrane of the Czechoslovak architectural press. The research traces Western ideas on urban¬ism in official journals: Architekt, Architektura ČSR, Sovětská architektura, Československý architekt and Projekt.

Theory and Reality of Czech and Slovak Urban and Spatial Planning since 1945

Architektúra & urbanizmus, as a journal published quarterly by a scholarly institution and declaratively focused on the theory of architecture, urban design and human environments, has represented from its very outset a well-anchored space for the discussion of contemporary architecture. In contrast to the monthly publications like the Slovak journal Projekt or its Czech counterpart Architektura ČSSR, it had at its disposal a greater chronological distance from the latest realisations, and its focus likewise allowed for more general thematization of current architecture. Nonetheless, it is true that texts addressing contemporary Slovak architecture, analysis of creative principles, architectonic forms, expressions or emerging trends, have appeared on its pages only sporadically and on an individual basis. Often, between individual contributions there could be a gap of up to a decade. In the first years of the journal’s publication, contemporary architecture was discussed mainly in connection with work in a historic environment, while special emphasis was placed on the formation of the city and questions of modern urban planning in the context of historic settlements. In this connection, the journal also published the results of the urban planning competitions of the era, such as the international ideal urban planning competition for the design of the southern district of Bratislava. The higher frequency of urban planning themes at this time was influence on one hand by the general social (and state) demand for the rebuilding and modernisation of cities, yet equally by the individual focus of the journal’s editors and the orientation of the two institutions that published the journal at the time: the Institute for Construction, Architecture and Urban Planning of the Slovak Academy of Sciences (ÚSTARCH SAV) and the ‘Department of Architectural Theory and Creation of the Living Environment’ of the Czechoslovak Academy of Sciences (ČSAV). Texts on contemporary architecture focusing on the analysis of the architectonic form of specific buildings began to appear in the journal only in the 1970s. In the first half of the decade, these were mostly generalized contributions balancing and evaluating the architecture of the past three decades since the end of World War II. Predominantly, the authors consisted of architectural historians from the universities in Bratislava or Prague. By the decade’s later half, attention came to focus on theoretical questions of creativity and architectural criticism, in this case addressed more often by researchers from the SAV and the ČSAV. The 1980s brought along a thematization of postmodern architecture, which persisted in the journal up until the start of the 1990s; here, the authors tended to be affiliated with the Department of Architectural Theory and Creation of the Living Environment (ČSAV). Reflection of postmodernism, in turn, was linked to the broader situation in the humanistic disciplines, in which a pluralism of approaches became the watchword of the Eighties. By the first half of the 1990s, the journal’s pages played host to confrontations between the contradictory standpoints of modernism and postmodernism, or more accurately postmodernism and the ‘new modernism’. Understandably, this period also witnessed a broad expansion of the circle of contributors, and a greater openness to international contributions: logically reflecting the change in society after 1989, one outcome of which was that contemporary architecture emerged as a theme not only for researchers and practitioners, but equally for the general public. Moreover, the fall of the Iron Curtain led to an immediate linking of the Slovak and Czech scenes with the themes of international architectonic discussion. The polarised discussion of this era was, however, the last time that such concentrated attention was turned toward contemporary architecture. As is clearly visible, the selection of themes, their frequency and the method of their treatment within Architektúra & urbanizmus has been conditions by many interior factors emerging from the current state of architectonic thought, yet equally by external ones such as the wider social situation or the personnel composition of the editorial board – or even the simple presence of personalities capable of reflecting contemporary architecture in the Czecho-Slovak context. The study reproduces the form, contents and the course of discussion on contemporary architecture in the journal throughout the past half-century. It also touches upon the personal and social ramifications that influenced the creation and publication of these texts. The focus here, though, is on the period from the 1970s up to the 1990s, and on the line of reflection of contemporary architecture that reacted directly to changes in the architectonic paradigm and assumed a polarising character. The texts addressing this topic are divided into three basic groups: historiographic, theoretical, or architectural criticism. Even here, we find a reflection of the development of writing about contemporary architecture in the journal, leading from history and large theories to critiques and partial theories. From the alternation, concentration or absence of individual genres, it is evident that the attention of the contributors over the past fifty years has moved from summary texts largely encompassing historical periods towards less sweeping texts focusing on selected phenomena. Other changes have been in the tone of contributions and the method through which research results are presented. Generalising texts formulated through abstract concepts, which were prevalent in the first decade, gradually have given way to contributions that address actual works and their real aspects. And a similar trajectory of development can be seen in the architectonic theories presented here. Increasingly, the authors of the texts moved away from the ambition to create and present a unified theory for contemporary architecture. While in 1971, there were still calls for formulation of a still more inclusive theory for all architecture and construction, by 2007 all that remained was a mere statement of such a theory’s absence. This interest in a single all-embracing theory of architecture culminated in the 1980s with the entrance of postmodernism into the Slovak environment, and it was at the same time that theorizing on architectural critique also reached its high point. Moreover, by the 1990s, attention shifted even further to the implementation of a criticism of treating architecture as a genre in itself. However, the general prevailing subject matter of the journal consisted of a retrospective view of contemporary architecture over a prospective one, with the ambition of directly shaping or directing the architecture of the moment. The end of the 1980s and the start of the 1990s could be regarded as the most productive period, at least in terms of the frequency of contributions on contemporary architecture. The articles published here at that time assumed the character of true architectural critique, programmatic statements and anticipatory texts all in one. In connection with the polemical or polarising character of the argumentation, as well as the close ties to active protagonists within Slovak architecture, this period could also be regarded equally as the most relevant in terms of relationships to immediate domestic architectural discussion. Perhaps the most consistent testimony to appear with relation to contemporary architecture was the monothematic double issue ‘Päť rokov po’ [Five Years After], published in 1995 and evaluating the first ‘free half-decade’ of Slovak architecture after 1989. The texts published in this issue were also the closest to direct architectural criticism. At the time, the focal point of discussion was given by the ‘dispute’ between the neo-Modernist and the regionalist-organic wings of Slovak architecture. In turn, the most striking reflection of international discourse on contemporary architecture, in particular its deconstructivist tendency, appeared in the monothematic double issue Berlín – Bratislava, narušené mesto [Disturbed City]. These two special issues of the journal could be regarded as the most complete records of the era’s thoughts on contemporary architecture in Slovakia that ever appeared in the journal – as well as forming two radically different methods of thematising contemporary architecture. While 5 rokov po is the overall original work of two authors and simultaneously the editors of the issue, Berlín – Bratislava, narušené mesto assumes the form of conference proceedings. The contributions addressing contemporary architecture published in the 1990s were also connected by a more or less pressing need to resolve the new social and cultural situation, and the position of Slovakia’s architecture in a European context. A number of authors in their argumentation made use of the conception of ‘centre vs. periphery’ or of the ‘cultural crossroads’. The study also reveals that contemporary architecture may have appeared in the journal without much planning, but never by chance. The texts that discussed contemporary architecture did not assume a fixed genre framework, and were not printed within the previously set rubrics. Their frequency, as well as their form, immediately reflected above all the personal research preferences of the journal’s creators, even as much as these preferences were directly connected to wider Czecho-Slovak as well as international architectural discussion. In these texts, it is possible to identify a significant phenomenological lineage in thinking of architecture drawing upon, or influenced by, the work of Christian Norberg Schulz and Kenneth Frampton, which persisted from the mid-1980s into the mid-1990s. At the same time, the fiftieth anniversary of the journal’s first appearance reflects an increasing concentration in authorial interest on the qualities of architectural form. The method of writing about contemporary architecture has essentially moved from investigating typological and social connections towards and analysis of formal manifestations and a classified direction, which culminated at the start of the 1990s. The rich array of genres and formats in writing about contemporary architecture, as well as their frequent alternation, can be regarded as proof of the journal’s expertise and independence, as well as confirmation of its openness and sensitivity with relation to the contemporary world and its themes. In turn, the shifting of views on contemporary architecture could also be viewed as a seismographic register of the shifts in the Slovak and Czech architectural scenes over time.The article describes the development of the theory of urban and spatial planning for cities and rural areas from the end of World War II. It notes that in the period shortly after the war, as well as the 1960s, the themes and outcomes of the work of Czech and Slovak theoreticians were fully comparable to contemporary work in Europe. After 1968, though, urban research and theory was forced into isolation from true international contact, and placed fully under the direction of political realities. This isolation had the result that urban design failed to reflect major themes connected with the social-scientific themes of the profession, which became clear as well in the subsequent era of post-Communist transformation. Even today, the profession of urban designer or planner finds it hard to define its identity, doctrines and even conceptual support for urban theory. …

Small Histories, Available Theories and Unsystematic Critique Contemporary Architecture in the Journal Architektúra & Urbanizmus

The study outlines the form, contents and course of discussions on contemporary architecture in the journal throughout its half-century of publication. Using a basic art-historical categorisation of texts as historiographic, theoretical and critical, the study situates the main themes of each period’s architectonic discussion. It shows that an interest in summary historical texts, which were characteristic for writing on contemporary architecture in the 1970s, gradually shifted towards a preference for more critical texts addressing changes in the architectonic paradigm and the confrontation of modernist and postmodern standpoints. In particular, attention focuses on the period from the 1970s through the 1990s, and on the topic of reflection of contemporary architecture, reacting directly to changes in architectural thought and often assuming a polarising stance. The study outlines the form, contents and course of discussions on contemporary architecture in the journal throughout its half-century of publication. Using a basic art-historical categorisation of texts as historiographic, theoretical and critical, the study situates the main themes of each period’s architectonic discussion. It shows that an interest in summary historical texts, which were characteristic for writing on contemporary architecture in the 1970s, gradually shifted towards a preference for more critical texts addressing changes in the architectonic paradigm and the confrontation of modernist and postmodern standpoints. In particular, attention focuses on the period from the 1970s through the 1990s, and on the topic of reflection of contemporary architecture, reacting directly to changes in architectural thought and often assuming a polarising stance.